An innovative approach for soon-to-be moms at Mercy Medical Center gave Makayla Tilghman the sort of pregnancy experience she wishes for all women: a chance to focus on the healthy development of her baby and enough support for her to be ready for the little one’s arrival.

Mercy’s Centering Pregnancy program opened at its downtown Baltimore campus about three years ago to combine the health care, interactive learning and community building needed to combat low birth weight and pre-term delivery for women at risk, especially Black moms in underserved areas.

The formula is pretty simple: The women get extended time and access to their medical team to ask questions and gain confidence while finding fellowship with one another through cooking classes, prenatal yoga and activities, such as creating plaster molds of their bellies for keepsakes.

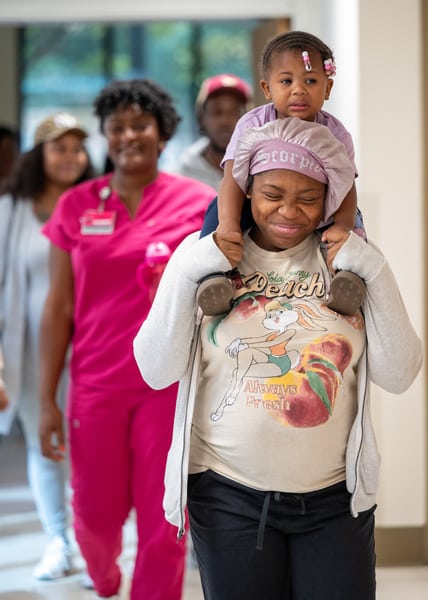

Tilghman, 21, said the Centering Pregnancy program gave her a “dream team” to help her navigate challenges tied to an unplanned pregnancy, low fetal birth weight and blood pressure that kept rising as she grew closer to delivering her daughter.

“They cared for me and my child to the fullest extent,” said Tilghman, whose daughter Leilani was born May 10 healthy and full-term.

The program aligns closely with the mission and values of the 150-year-old Catholic hospital, said Erin Tribble, Mercy’s director of pastoral care. The Centering Pregnancy approach incorporates the principles of Catholic social teaching to create conditions for human flourishing at both the individual and community level, she said.

“By providing excellent prenatal care and other resources, especially among an often-vulnerable population, Centering recognizes the dignity of expectant mothers and their unborn children and safeguards their lives from tragic outcomes, such as infant or maternal mortality,” Tribble said.

The Centering Pregnancy program has served about 300 pregnant women and their babies since it launched as an extension of Mercy’s Family Childbirth & Children’s Center.

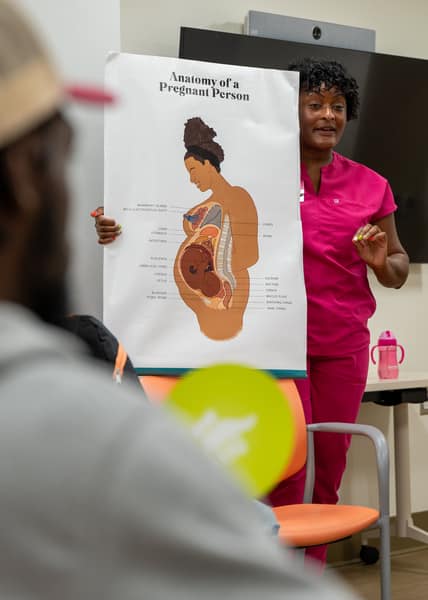

Kia N. Hollis, a certified nurse midwife who specializes in obstetrics and gynecology, oversees the program. She said women who participate in the program are less likely to have a premature baby and their rates of breastfeeding are higher than they otherwise would be. Other outcomes include lower rates of gestational diabetes and fewer babies born by cesarean section.

The soon-to-be moms enrolled in the program receive prenatal care that involves visits much longer than a typical doctor’s appointment, so they can engage more fully with their providers and ask the questions on their minds, Hollis said. They receive health assessments and gather together in sessions facilitated by a healthcare provider. They talk about nutrition and pregnancy discomforts, stress management and mindfulness, labor and delivery, and breastfeeding and infant care.

For Hollis, the relationships the women in the program form with one another are key to its success. She said participants become friends, share job opportunities and connect to one another in faith. The setting also allows them to feel comfortable to open up in ways medical providers don’t always see in typical prenatal visits. For example, Hollis said one woman began to trust the providers enough to disclose domestic violence in her relationship – and seek help.

“Centering really allows us to address the social determinants of health that aren’t addressed in the routine prenatal visit,” Hollis said. “The goal of the program is not only to reverse negative outcomes, but to establish a positive social network and positive connections that persist beyond pregnancy.”

The approach was developed two decades ago by a Boston-based nonprofit called the Centering Healthcare Institute that works to improve health, transform care and disrupt inequitable systems. The institute says the Centering approach provides better care and better health outcomes at a lower cost – with the potential to prevent more than 150,000 of all preterm births and save the healthcare system $8 billion a year.

At Mercy, Tilghman said she built relationships on which she continues to lean, and she regularly draws on the guidance she received as a first-time mother. Because she was a student at Morgan State University when she became pregnant and away from her family in Philadelphia, the program became a lifeline.

“I instantly fell in love with the hospital and staff,” Tilghman said. “They were absolutely amazing and God-sent.”

Maryland Snapshot

- 1 in 10 births are preterm.

- About 10.2 percent of Maryland babies are born before 37 weeks – slightly above the national average. (March of Dimes, 2023)

- Infant mortality remains high.

- Maryland’s infant mortality rate is 6.2 per 1,000 live births; for non-Hispanic Black infants, it rises to 10.3 per 1,000. (Maryland Department of Health, 2022)

- Persistent racial disparities in maternal health.

- More than half of maternal deaths in Maryland from 2010 to 2017 were among non-Hispanic Black women, despite representing fewer than half of births. (National Library of Medicine, 2023)

Read More Local News

Copyright © 2025 Catholic Review Media