PHILADELPHIA (OSV News) — A newly released Vatican commission report on the issue of women deacons ultimately shows the profound theological mystery of Christ’s relationship to the church, as well as the rediscovery of the long-dormant diaconate itself, experts told OSV News.

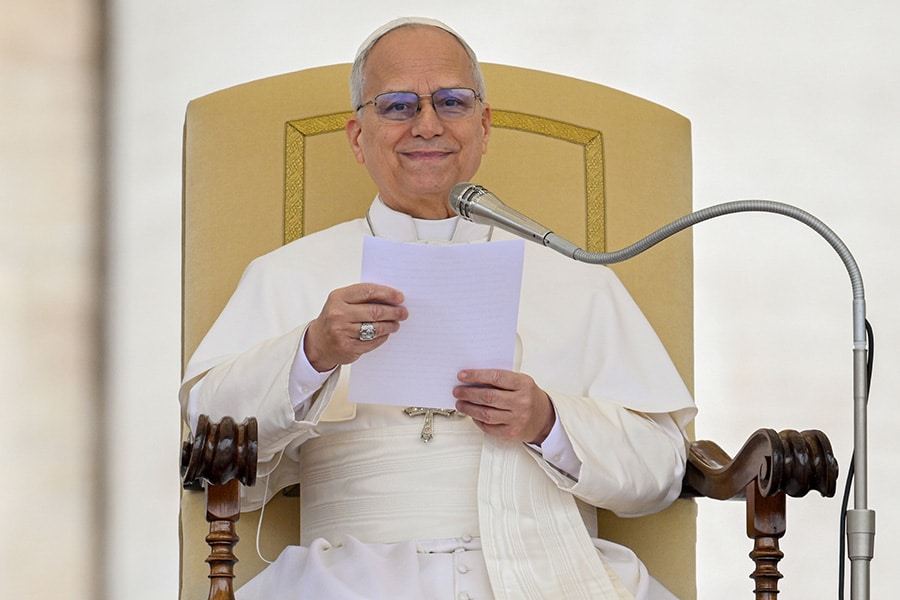

At Pope Leo XIV’s direction, the Vatican published a seven-page synthesis report from the “Study Commission on the Female Diaconate” on Dec. 4.

Established by Pope Francis in 2020, the commission continued the work of a previous group in examining the history of women deacons in the New Testament and the early Christian communities.

The commission — which included five women and five men, among them two permanent deacons from the United States and three priests — voted against ordaining female deacons and deferred the issue to “further theological and pastoral study.”

In addition, the commission stressed the final decision rests with the Catholic Church’s magisterium, and called for expanded participation of women in other areas of the church’s life and ministry.

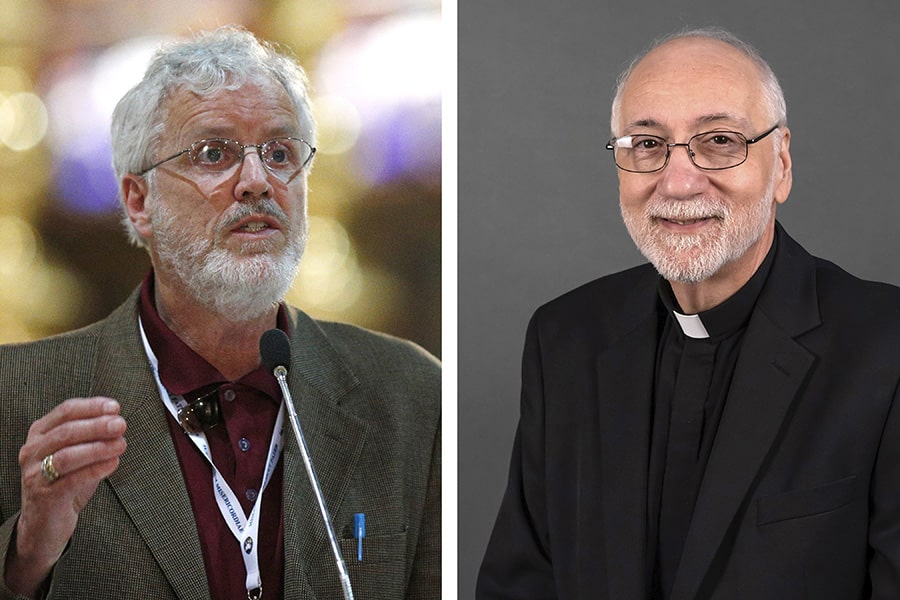

Addressing the issue of women deacons requires “the perspective of discovering what Our Lord would want,” Deacon Dominic Cerrato, one of the American permanent deacons to serve on the commission, told OSV News Dec. 4. “In other words, we simply can’t say, ‘This is what people want.’ This is a theological question.”

The deacon is director of Diaconal Ministries, which works to support deacons in their ministry, and recently served as head of the diaconate office of the Diocese of Joliet, Illinois.

The synthesis report itself, citing Pope Benedict XVI, also affirms the issue is primarily a theological one: “We know, however, that a purely historical perspective does not allow us to reach any definitive certainty. Ultimately, the question must be decided on a doctrinal level.”

Deacon Cerrato and Deacon James Keating, spiritual theology professor at Kenrick-Glennon Seminary in St. Louis, have written and consulted extensively on the permanent diaconate and seminary formation. They noted that simply pointing to historical references of women deacons in the early church can obscure the extensive theological dimensions of the issue.

In fact, those historical references aren’t always well understood by many in the first place, they said.

While the diaconate traces its roots to the commissioning of seven men as such in Acts 6:1-7, deaconesses “didn’t appear until the fourth century,” explained Deacon Cerrato.

Their emergence was due to “cultural conditions which tended to segregate the sexes more than we do today,” said Deacon Keating — and, said Deacon Cerrato, due to the fact that at the time, baptism, then performed as a full immersion into water, “was done in the nude.

“And so it was important that bishops, for modesty’s sake, didn’t see the women who came up for baptism,” said Deacon Cerrato.

“There is no evidence that I have seen which places these women deaconesses within the liturgy of the Western church functioning as the proclaimers of the Gospel and serving at the altar during the preparation of the bread and wine,” said Deacon Keating, who also served on the commission.

“The question is not whether or not there were deaconesses in the early church. There certainly were; can’t be denied,” said Deacon Cerrato. “The question is whether they were the equivalent to the male diaconate.”

Yet “they related to the bishop very differently as well as to the presbyterate. … There was no hope of them going on to the priesthood,” he said. “So fundamentally, they were a … different kind of thing than the male deacon.”

Once the liturgical form of baptism changed to its present rite, which no longer requires full immersion, the deaconesses “moved on into what would later be religious orders,” said Deacon Cerrato. “So they existed for a specific reason and then faded off.”

As the church expanded, the deacons themselves also gradually declined, starting in the fifth century. In 1967, Pope Paul VI formally reestablished the permanent diaconate in the Latin Church, following the Second Vatican Council, with calls for such renewal first issued during the Council of Trent and gaining momentum during the Second World War.

The permanent diaconate, along with the presbyterate (priesthood) and episcopacy (bishops), is now one of the three degrees of the sacrament of holy orders in the Catholic Church.

Such historical context is crucial, said Deacon Keating, who stressed that “the restoration of the diaconate” as a whole “is only 60 years old.”

“The church is still discovering its beauty and its full mission,” he said. “The gathering of this commission indicates the church is trying to listen to the Holy Spirit as the diaconate … begins to penetrate the imagination of the church and its members.”

Deacon Keating said the study commission “appears to have taken into consideration both the movements of secular ideas (women’s rights and equality) and the historical and theological developments regarding diaconal identity.”

In doing so, he said, “the commission meditated upon a vital truth: Christ is the bridegroom of the church.”

The Catechism of the Catholic Church — citing the prophets, St. John the Baptist, St. Paul and the words of Christ himself — states that the unity of Christ with his church is “often expressed by the image of bridegroom and bride,” with Christ joining the church to himself in “an everlasting covenant.”

“Christ’s intention is to espouse those who have entered the mystery of faith as his bride,” Deacon Keating explained. “In their service at the altar, the ordained sacramentally embody Christ’s own spousal self-gift. “

Crucially, said Deacon Keating, “the masculine identity of Christ is intrinsic to his mission as bridegroom,” and as a result, “fundamentally, women cannot become deacons.”

Deacon Cerrato observed that “if you take away this beautiful imagery of Christ and his bride, the church — where, of course, the head is represented by the clergy, and the church is the bride” in “beautiful nuptial imagery” — the result is “a theological transgenderism.”

Deacon Keating said the Eucharist communicates the identity of Christ as the bridegroom of his church — and that “this spousal self-offering of the one Christ takes the mission of three grades of holy orders acting in unity at the altar to express it.”

He stressed that “rightfully, many desire to correct any wrongs done to women where offices and ministries were denied to them unjustly” — but, he said, “the liturgy has not carried injustice toward women within it.

“It has only carried the salvific acts of Christ the bridegroom within it, acts of self-donation toward his beloved bride,” said Deacon Keating.

Deacon Cerrato said it’s also key to clarify “what constitutes justice” — adding, “for us, God constitutes justice.”

“The very first revelation that God gave is that he created man in his image, male and female,” said Deacon Cerrato. “And so the church understands there’s a complementarity in these two, which society rejects. Society wants to say that equality means sameness. And the church says, ‘No, it doesn’t mean sameness in the sense of the egalitarian sense. It means that there’s a sameness, there’s an equality of dignity, but there’s a complementarity to it.’ And understanding the complementarity gives us insight into the very nature of God.”

Ruling out women as deacons doesn’t preclude a life of holiness in Christ, said Deacon Keating.

“Women of course can be Christ-like due to the sacraments of initiation,” he said. “Empowered by this grace, women image Christ morally in daily life unto sanctity.

Deacon Keating, echoing the commission’s synthesis report said that “many roles within the church outside the Eucharistic liturgy, where ordination is essential, should be open to women.

“We have recently seen Pope Francis place women in positions of governmental power and influence,” he said. “No doubt Pope Leo will continue this.”

Read More Vatican News

Copyright © 2025 OSV News