Cardinal Keeler served as the spiritual shepherd of the Baltimore archdiocese from 1989 until his retirement in 2007.

Archbishop William E. Lori, one of Cardinal Keeler’s two successors, said one of the great blessings of his life was coming to know Cardinal Keeler, whom he met when the cardinal was bishop of the Diocese of Harrisburg, Pa., and Archbishop Lori was priest-secretary to Washington Cardinal James Hickey.

When Cardinal Keeler became archbishop of Baltimore, Archbishop Lori said he learned of “his prowess as a church historian coupled with his deep love and respect for the history and heritage of the Archdiocese of Baltimore.”

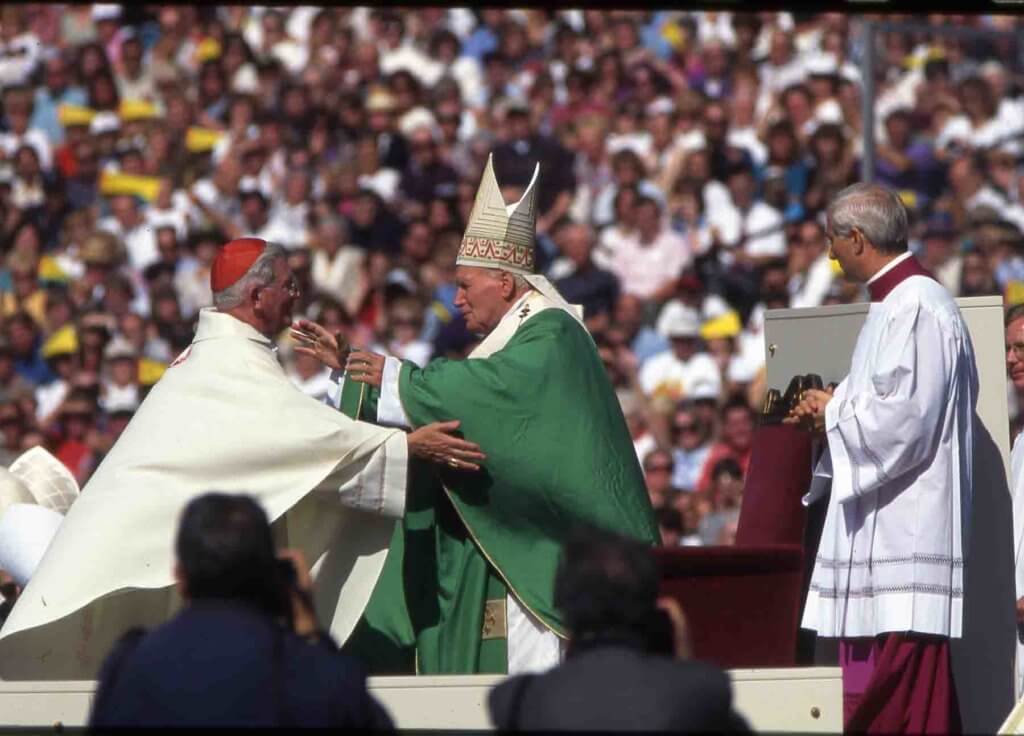

Among Cardinal Keeler’s many accomplishments in the Baltimore archdiocese, Archbishop Lori highlighted “the wonderful visit of Pope St. John Paul II to Baltimore in 1995, the restoration of the Basilica of the Assumption and the creation of Partners in Excellence which has helped thousands of young people from disadvantaged neighborhoods to receive a sound Catholic education.”

“When I would visit the cardinal at the Little Sisters of the Poor (in Cardinal Keeler’s retirement), I gave him a report on my stewardship and told him many times that we were striving to build upon his legacy – a legacy that greatly strengthened the Church and the wider community,” Archbishop Lori said in a written statement.

Pennsylvania roots

Born in San Antonio, Texas, and raised in Lebanon, Pa., Cardinal Keeler knew from an early age he was called to the priesthood. In a 2005 interview with the Catholic Review, he recalled visiting his grandfather’s farm in Illinois when the local Catholic pastor stopped by for a visit – pointing to the 4-year-old boy and announcing that he would one day become a priest.

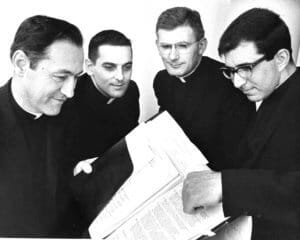

After graduating from Lebanon Catholic High School in 1948, Cardinal Keeler entered St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, seeing priestly service as a way of expressing his gratitude to God.

“I wondered about a way of saying thank you to (God) and giving back to the church the gifts that God had given to me,” Cardinal Keeler remembered. “It was as simple as that. For me, becoming a priest was not complicated.”

Cardinal Keeler was ordained a priest in Rome July 17, 1955. He served as assistant pastor of Our Lady of Good Counsel in Marysville, Pa., before taking on other assignments as secretary to Harrisburg Bishop George L. Leech and as a “peritus,” or special advisor, during Second Vatican Council meetings in Rome.

Cardinal Keeler served as pastor of Our Lady of Good Counsel from 1964 to 1965, and was named vice chancellor and then vicar general and auxiliary bishop of the Harrisburg Diocese. St. John Paul II appointed him bishop of Harrisburg Nov. 10, 1983, and archbishop of Baltimore April 11, 1989. The pope elevated Cardinal Keeler to the College of Cardinals in 1994. His episcopal motto was, “Do the work of an evangelist.”

Putting Baltimore on the map

Father Michael White, pastor of the Church of the Nativity in Timonium and Cardinal Keeler’s first priest-secretary in Baltimore, said Cardinal Keeler “put Baltimore on the map in the Catholic Church.”

Father White noted that in addition to the papal visit, Cardinal Keeler hosted spiritual gatherings in Baltimore in the late 1990s with St. Teresa of Kolkata and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople. Leaders within the Catholic Church and from other faith traditions regularly visited him in Baltimore and “not a day went by” when bishops from other parts of the country didn’t call for the cardinal’s advice, Father White said.

No Baltimore archbishop since Cardinal James Gibbons attracted as many key leaders to Baltimore as Cardinal Keeler, Father White said.

“Pope John Paul loved Cardinal Keeler,” Father White remembered. “He used to call the cardinal ‘Baltimore.’”

the pope’s historic 1995 visit to Baltimore. (CR file)

The 1995 papal visit to Baltimore – at the invitation of Cardinal Keeler – was one of the cardinal’s proudest moments. The pope celebrated Mass at Oriole Park at Camden Yards, visited the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen and the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, shared a meal at Our Daily Bread and encouraged seminarians at St. Mary’s Seminary in Roland Park.

Harold A. “Hal” Smith, former executive director of Catholic Charities, remembered that during the pope’s meal at Our Daily Bread with approximately 20 representatives of various Catholic Charities programs, everyone froze in the presence of the pontiff.

“Nobody knew what to say,” Smith remembered. “The cardinal had a wonderful moment of hosting the group when he spearheaded the conversation by asking the pope a question. The people would ask the cardinal a question, who would then address the Holy Father.”

It took about 10 minutes before everyone realized they could talk directly to the pope, Smith said.

“The cardinal made it all work,” he said.

Fundraising success

A prodigious fundraiser, Cardinal Keeler established what is now known as the Archbishop’s Annual Appeal. In 1997, he launched a major capital campaign known as Heritage of Hope that raised more than $137 million from more than 39,000 gifts and pledges.

The cardinal also established the Partners in Excellence program, which provides tuition scholarships for children in inner-city Catholic schools. Since its inception in 1996, Partners in Excellence has provided more than $26 million in tuition assistance.

Father White remembered that Cardinal Keeler viewed fundraising as an important part of his job, one that he didn’t avoid. During one campaign, Father White recalled, Cardinal Keeler met with a prominent leader to ask for a significant amount of money – more than had been asked of anyone else. During their meeting, the cardinal slid a card across the table to the potential donor with the suggested amount. The man looked at it and agreed to the contribution.

“After the guy left, I said, ‘You must have been so nervous,’” Father White said. “The cardinal said, ‘Oh, I was – because I doubled the number. At the last minute, I thought, ‘Why not?’”

Donors supported the cardinal’s initiatives because they knew and trusted him, Father White said.

Basilica restoration

One of the cardinal’s last major efforts was the $32 million campaign to restore the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Baltimore.

After more than two years of construction, the building was rededicated on Nov. 4, 2006 – 200 years after the basilica’s cornerstone was laid. More than 240 bishops from across the nation gathered in Baltimore for the celebration, marking the first time all the country’s bishops gathered in the basilica since 1989 when the archdiocese marked its bicentennial.

During the restoration, the basilica’s dome skylights, which had long been closed, were reopened. Stained-glass windows that had been installed in the 20th century were relocated to a new church at St. Louis, Clarksville, to make way for clear glass windows that allowed the basilica’s interior to be bathed in natural light in keeping with the original vision of Archbishop John Carroll and architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

In addition to updating the basilica’s infrastructure, long-lost statues of angels were recovered and restored. The interior was repainted, white marble floors were installed, the organ was restored and statues of St. John Paul II and St. Teresa of Kolkata were added. A new chapel dedicated to Our Lady, Seat of Wisdom, was created in the basilica’s undercroft and the building’s exterior was illuminated at night.

Cardinal Keeler, who once said there is “no place on earth like the basilica,” received the personal blessing of St. John Paul II for the restoration project and viewed it as one of his most important undertakings.

of the Blessed Virgin Mary as it undergoes a restoration in the mid-2000s. (CR file)

“I saw this as the most precious place of worship in the United States,” Cardinal Keeler told the Catholic Review in a 2005 interview. “The basilica will be a main attraction for pilgrims and visitors. They will stop here to visit and to pray, and they will return home to tell others that they visited this cathedral.”

Michael Ruck, chairman of the Basilica of the Assumption Historic Trust Board of Trustees, said the basilica’s restoration was possible “only through Cardinal Keeler’s heroic and extraordinary efforts.”

The cardinal recognized that the basilica was the preeminent symbol of religious freedom in the United States, Ruck said, and that the archdiocese had a duty to care for it.

“The cardinal knew that as important as the past is, it’s just as important to know there’s a church in the future,” Ruck said.

A few years after the basilica was rededicated, the Pope John Paul II Prayer Garden was established on the grounds of the former Rochambeau apartment building on Charles Street, a structure erected in 1906 and acquired by the archdiocese in 2001. Cardinal Keeler underwent a public struggle with a small group of historic preservationists who opposed tearing down the long-vacant structure. He ultimately won a legal battle that allowed the building to come down to make way for the prayer garden, which featured a large bronze statue of St. John Paul II modeled on the pope’s visit to Baltimore.

“The building that was there, as everybody in the neighborhood knows, was a dump,” Cardinal Keeler told the Catholic Review in a 2008 interview. “Thank heavens, it is now history.”

Cardinal Keeler said he viewed the prayer garden as a place of solitude in an often-noisy city.

“I pray that people of every background, of every race and creed will be able to use the garden,” he said. “Pope John Paul II himself was one who promoted interfaith harmony in a very personal way.”

Ecumenical and interfaith dialogue

Cardinal Keeler was himself a champion of interfaith and ecumenical understanding, regarded as one of the world’s leading figures in the field.

When Jewish conductor Maestro Gilbert Levine, the “pope’s conductor,” visited Baltimore in 2000 to conduct a special performance of Haydn’s “Creation” for an international interfaith musical pilgrimage, he asserted that Cardinal Keeler’s “very body is in the rhythm of interfaith.”

Cardinal Keeler was named a member of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity in 1994. He also served as episcopal moderator of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs from 1984 to 1987. While leading that group, Cardinal Keeler arranged for St. John Paul II to meet with Jewish leaders and Protestant representatives in South Carolina, and attend an interfaith ceremony in Los Angeles during the pope’s 1987 visit to the United States.

After Catholics and Lutherans agreed to a Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification in 1999, Cardinal Keeler and Bishop George Paul Mocko, then bishop of the Delaware-Maryland Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, nailed a copy of the document to the doors of the Baltimore Basilica and also Christ Lutheran Church in Fells Point.

“He knew how to listen,” said Rabbi Joel Zaiman, rabbi emeritus of Chizuk Amuno Congregation, Baltimore. “He heard. He understood, and he responded genuinely and generously. He was always available when I called – wherever he was – oftentimes, Rome.”

It was important to the Jewish community that the cardinal had the ear of the pope, Rabbi Zaiman said.

during the patriarch’s 1998 visit to Baltimore. (CR File)

Rabbi Abie Ingber of Xavier University, Cincinnati, and Dr. William Madges, of Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia, curators of a national exhibition highlighting St. John Paul II’s relationship with Jews, honored Cardinal Keeler in 2010 for his work promoting Catholic-Jewish understanding by presenting him with a bronze medallion. The cardinal had worked to promote the exhibit, which was featured at Baltimore’s Jewish Museum of Maryland.

Rabbi Ingber noted that one of the titles for the pope is “pontifex maximus,” which means “master bridge builder.” Recognizing Cardinal Keeler’s contributions as a bridge builder, the rabbi joked that if there was such a title as “pontifex almost maximus,” the cardinal should have it.

For part of his retirement, Cardinal Keeler lived at Mercy Ridge Retirement Community in Timonium, adorning his walls and shelves with gifts such as a replica of a menorah that he helped bring to the Pontifical North American College in Rome. He later moved to St. Martin’s Home for the Aged in Catonsville.

Abuse crisis

Just as he worked to rebuild historic structures and respect among people of different faiths, Cardinal Keeler also worked to rebuild trust in the wake of the clergy child abuse crisis that broke in 2001.

Cardinal Keeler strengthened archdiocesan policies related to child and youth protection, requiring all employees and volunteers who work with children to undergo safe-environment training through a new program called “STAND.” Fingerprinting of employees became mandatory, and background checks were also required for both employees and volunteers.

In September 2002, Cardinal Keeler became one of only a handful of bishops in the nation to release the names of clergy – living and dead – who had been “credibly accused” of the sexual abuse of children. Fifty-seven names were published in the Catholic Review and made available to the secular press – a decision that was met with considerable consternation from some.

“He recognized that people had a right to know what happened, what was known and what was done,” said Daniel Medinger, who was editor/associate publisher of the Catholic Review at the time the names were printed. “He knew that there was only one way to do that, which was to tell the truth.”

Medinger called the cardinal’s decision to publish the names “incredibly brave” and “incredibly wise.”

“The problems now facing some other dioceses didn’t really happen here in the same way,” Medinger said, “and I think that’s because there wasn’t the perception of cover-up. Because of the cardinal’s openness and years of building trust within the media, he was able to accomplish his goal of getting the information out.”

Cardinal Keeler became the first cardinal in the nation to take the witness stand in a criminal trial related to the clergy sex abuse scandal when he testified for the defense in the attempted murder of Maurice J. Blackwell, a defrocked priest accused of sexually abusing Dontee D. Stokes. Stokes shot and wounded Blackwell, but a Baltimore City Circuit Court jury found Stokes not guilty in 2003.

Cardinal Keeler had first suspended Blackwell from ministry in 1993 when Stokes accused him of sexual abuse, but later reinstated Blackwell as pastor of St. Edward in Baltimore despite a recommendation to the contrary from a lay review board.

On the witness stand, the cardinal said he regretted his action in reinstating Blackwell.

“Given the same information we have now, I certainly would not do that again,” said the cardinal, who also apologized to Stokes on the witness stand. He had earlier met with Stokes privately and also shook his hand before and after testifying.

In 2004, the cardinal led a “day of atonement,” asking forgiveness for sins the church had committed against victims of clerical sex abuse.

In the public arena

With a keen interest in promoting pro-life, education and social justice, Cardinal Keeler was active in the legislative process. Former chairman of the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference when he was bishop of Harrisburg, he took on a similar role in Baltimore as chairman of the Maryland Catholic Conference, the Annapolis-based legislative lobbying arm of the state’s bishops.

The cardinal met with mayors and governors wrote letters to lawmakers and worked behind the scenes to advance initiatives such as funding for non-religious textbooks and technology in the state’s nonpublic schools.

Mary Ellen Russell, executive director of the Maryland Catholic Conference, described Cardinal Keeler as an “extraordinary” diplomat.

“He had an amazing skill to be able to promote the principles that the church upholds – especially the value of life – in an appealing, convincing, yet firm, manner,” Russell said.

Cardinal Keeler met and prayed with convicted murderer Wesley Eugene Baker on death row in 2005, using the dramatic visit to call on then-Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. to spare Baker’s life.

Speaking to reporters outside Maryland’s Supermax prison in Baltimore moments after meeting with Baker, Cardinal Keeler said he and other bishops were compelled to plead for mercy because of the Catholic Church’s respect for the sanctity of all human life.

The plea was ignored and Baker was executed one week after the cardinal prayed with him.

Russell said the cardinal tried to live his motto, “Do the work of an evangelist,” “by conveying the appeal and the beauty of the Gospel message through his words and actions.”

Cardinal Keeler was elected president of what is today known as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops Nov. 17, 1992, after serving three years as vice president.

Cincinnati Archbishop Daniel E. Pilarczyk, in a 2005 interview with the Catholic Review, remembered that Cardinal Keeler did not come to his leadership post with his own agenda.

“That’s not the president’s job,” said Archbishop Pilarczyk, who was president of the bishops’ conference during the time Cardinal Keeler was vice president. “The job is to get the bishops’ business done. Under his leadership, you got the work done. There was no messing around.”

During his three-year tenure as president, Cardinal Keeler laid the foundations for dealing with priest sexual abuse by forming an ad hoc committee to deal not only with priest sexual abuse, but to address sexual abuse throughout society.

Cardinal Keeler also joined two other Catholic prelates in meeting with President Bill Clinton in 1993. He won an apology from Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders for remarks on a television interview in which she dismissed the Catholic position on abortion as that of a “celibate and male-dominated church.” He also asked fellow bishops to take up a special collection for relief efforts in Central and Eastern Africa and spoke out in support of interfaith understanding and against abortion.

He became a mentor to future bishops such as Wilmington Bishop W. Francis Malooly, former auxiliary bishop of Baltimore.

“I was always learning from him,” Bishop Malooly said. “I was struck by how thoughtful he was. For someone who was involved in so many things locally, nationally and internationally, he always took time to be conscious of the people around him.”

Cardinal Keeler served as president of the Catholic Near East Welfare Association, chairman of the board of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, co-chairman of the Religious Alliance Against Pornography, a member of the National Interreligious Leadership Initiative for Peace in the Middle East, and a member of the bishops’ Task Force on Catholic Bishops and Catholic Politicians.

In standing up for the sanctity of life, the cardinal began what was then known as Project Rachel, a post-abortion ministry in the Archdiocese of Baltimore and his former Diocese of Harrisburg, Pa. He also supported the Gabriel Network, which provides assistance to women facing crisis pregnancies and their children, and served two terms as chairman of the bishops’ Committee for Pro-Life Activities, most recently in 2003-06.

In a 2005 homily at the Vigil Mass for the March for Life in Washington, D.C., Cardinal Keeler said Americans are increasingly becoming aware “of the vast network of lies that have been spun and fortified to sustain the illusion that abortion is somehow a good, or at least a morally neutral procedure; that it is a standard part of health care and family planning; that it is a proper exercise of a woman’s freedom; that it is a solution to intractable social problems.”

It is, he said, none of those things.

“What it is,” Cardinal Keeler said, “is an unfettered right to take an innocent, human life from the mother’s womb.”

Support for education

Archbishop Spalding High School in Severn in 2004. (CR file)

Cardinal Keeler, who served as a bus driver for a parish school after he was first ordained, gave his blessing to several innovative educational programs within the Baltimore archdiocese, including one for children with special needs – PRIDE (Pupils Receiving Inclusive Diversified Education.)

Mary Jo Hutson, a former principal of St. Anthony School in Hamilton where the first PRIDE program was launched, said in an earlier interview with the Catholic Review that the cardinal used a gift for hospitality to win support for PRIDE, Partners in Excellence and other initiatives.

“There is no question that he was an engaging presence at any gathering,” said Hutson, who died in 2015. “A crowd brought a distinct sparkle to his eye.”

Hutson, a former associate superintendent for Catholic schools, said the cardinal’s greatest legacy is his gift for making people feel recognized, known and remembered.

“This, I think, is the hospitality that must precede all of our efforts to evangelize,” Hutson said.

During his tenure, several Catholic schools closed. Several others opened, including St. Ignatius Loyola Academy, Mother Seton Academy, Sisters Academy, Our Lady of Grace School, Cristo Rey Jesuit High School and School of the Incarnation.

Mary Pat Seurkamp, former president of what is now Notre Dame of Maryland University, said Cardinal Keeler was “very attentive” to implementing Ex Corde Ecclesiae, a 1990 apostolic constitution on Catholic higher education which set norms to assure the Catholic mission and identity of Catholic colleges and universities. He worked with leaders of Notre Dame, Loyola University Maryland and Mount St. Mary’s University on implementing the constitution.

“He was very thoughtful about how to address these issues,” Seurkamp said. “He recognized that higher education needed to be a place where ideas could be expressed, but we also had to do things consistent with the teachings of the church.”

When Loyola University Maryland selected former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani as its commencement speaker and recipient of an honorary degree in 2005, Cardinal Keeler directed that no representative from the Archdiocese of Baltimore be present at the commencement exercises because of Giuliani’s support for keeping abortion legal.

Seurkamp, whose family has had close ties to the cardinal going back to his Harrisburg days, said she periodically called the cardinal to get his advice on difficult issues, including controversial speakers at the university. She also enjoyed sharing good news with him, she said.

“He was a very holy man,” she said. “He had a deep spirituality and holiness about him. He was also very smart and strategic.”

Diverse church

The cardinal reached out to African American Catholics, Hispanics and young people in active ways. Therese Wilson Favors, former archdiocesan director of the Office of African American Catholic Ministries, noted that the cardinal established the office as the primary focus of evangelization and leadership development within the African American community. He supported other outreach efforts such as Operation Faith Lift, an evangelization effort in black parishes; and Harambee, a youth program.

Cardinal Keeler established the Office of Hispanic Ministry within the archbishop’s administrative department and made efforts to bring more Spanish-speaking priests to the archdiocese. He was a strong supporter of legislation such as the DREAM Act, and he invited prominent bishops from Spanish-speaking countries to serve as homilists at the annual archdiocesan Mass celebrating Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Maria Johnson, former director of the Office of Hispanic Ministry, said the cardinal had a special interest in the Hispanic community because in his youth, the cardinal befriended a Mexican seminarian. When the two traveled, Cardinal Keeler witnessed discrimination against his friend.

“With various issues – especially immigration – he always wanted to take part in some way with public action,” Johnson said.

Through Cardinal Keeler’s leadership, the Archdiocese of Baltimore established a sister diocese relationship with the Diocese of Gonaives, Haiti, in 1997. With assistance from the Mortel Family Charitable Foundation, The Good Samaritans School was built in Haiti. A trade school and a literacy school were also established. Many parishes within the archdiocese have partnerships with Haitian faith communities, assisting with feeding programs, education and evangelization.

“He’s always wanted to help the people of Haiti as much as possible,” said Deacon Rodrigue Mortel, missions director for the Baltimore archdiocese. “He really facilitated us in getting the funds for the Good Samaritans School.”

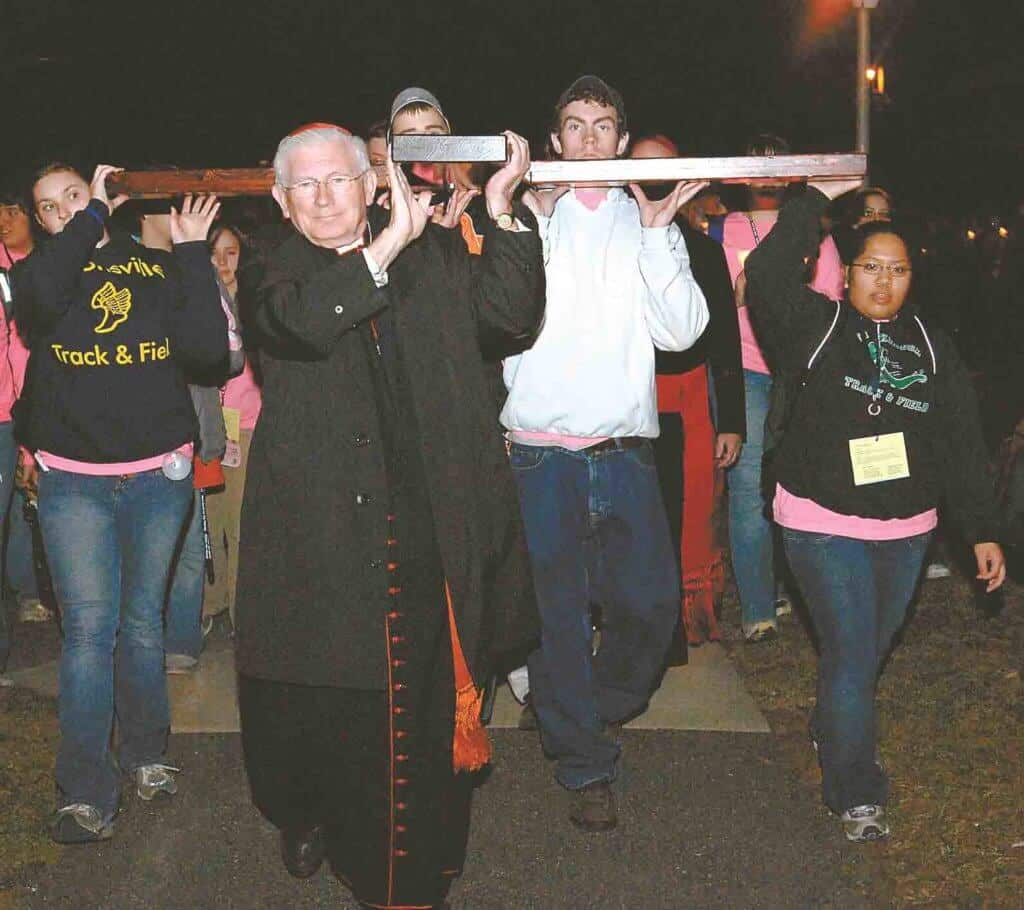

Mark Pacione, former director of the Office of Youth and Young Adult Ministry who died in 2014, told the Catholic Review in an earlier interview that Cardinal Keeler understood young people represented the future of the church. The cardinal served as chairman of the eighth World Youth Day, held in Denver in 1993. In Baltimore, he started and participated in the youth and young adult pilgrimage, an annual event held the Saturday before Palm Sunday to give young people a chance to listen to faith testimonies and carry a large cross through the street of the city.

The cardinal earned the respect of young people, Pacione said.

“He was their archbishop,” Pacione said. “He was their leader.”

Gentle leader

Although many who knew Cardinal Keeler described him as an essentially shy person, they noted that he was warm and congenial with a good sense of humor.

Monsignor Joseph Luca, pastor of St. Louis, Clarksville, remembered driving to a radio studio to record a commercial promoting RENEW, a program designed to help foster faith. The cardinal took the wheel.

“We pulled up to the studio and the owner of the studio came to my side of the car and said, ‘Oh, your eminence. We are so glad to see you.’”

Monsignor Luca was embarrassed, the priest said, but the cardinal thought it was “hysterical.”

Father Leo Patalinghug, leader of the Grace Before Meals apostolate, remembered that the cardinal sometimes took Baltimore seminarians out to dinner in Rome.

“We were walking home, and he was telling us this story and we all got to laughing so hard that he had to stop and he was holding onto the wall he was laughing so hard,” said Father Patalinghug, who studied at the Pontifical North American College in Rome. “We all were just amazed to see the utter joy that he could exude.”

Father Patalingug said the cardinal was also a deeply spiritual man – someone who knew when it was time to laugh and when it was time to pray.

“I was struck by his desire to be seen as one who was a spiritual father to his people as opposed to simply being the authority figure,” said Monsignor Luca, noting that 38,000 people throughout the archdiocese participated in the RENEW program during its three-year operation. Many priests also participated in the Emmaus program, an initiative promoted by the cardinal to provide support to clergy.

Later years

Cardinal Keeler suffered serious health problems in the latter years of his ministry. He underwent knee replacement surgery in 2005 and had to have brain surgery in 2006 following a car accident in Italy that resulted in the death of a friend, Father Bernard Quinn of Harrisburg.

In the early part of his retirement, Cardinal Keeler remained focused on many of the same priorities he had always held: promoting better relations between the Catholic and Jewish communities, celebrating Mass every day and staying in touch with friends.

Many of his family, friends and religious leaders from around the world gathered in Baltimore in 2011 to celebrate the cardinal’s 80th birthday.

“You have been and continue to be a star,” Archbishop Pietro Sambi, former apostolic nuncio to the United States, told Cardinal Keeler during the birthday celebration, “a light of hope, not only for the church, but also for the community at large.”

In his final years, one of the U.S. church’s great communicators was frustrated by finding it difficult to find the words to express himself.

“His final years of illness were lived in silent, Christ-like dignity and acceptance to the will of God,” said Cardinal Edwin F. O’Brien, Cardinal Keeler’s immediate successor.

Referring to Cardinal Keeler’s accomplishments as “monumental,” Cardinal O’Brien added that he prays that the cardinal will “enjoy a joyful, eternal rest in the Lord he served so generously.”

Jennifer Williams, former Catholic Review web editor, contributed to this story.

Email George Matysek at gmatysek@CatholicReview.org

Also see:

The Archdiocese of Baltimore’s tribute page to Cardinal Keeler may be found here.

Copyright © 2017 Catholic Review Media