“… at known risk … intense shelling … disregarded opportunities to seek positions of relative security … utter disregard of personal safety.”

Passages such as these conjure images of the fierce soldier, advancing against the enemy, rallying comrades to victory under unthinkable conditions.

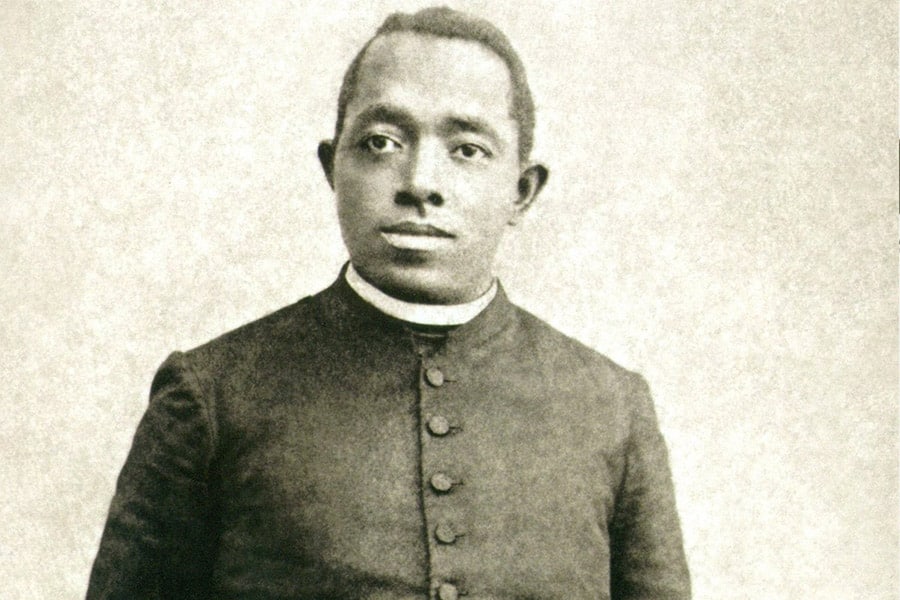

Those quotations, however, come from citations honoring a young Conventual Franciscan priest from Baltimore, descriptions of daily realities. Under enemy fire in World War II, he bore the instruments of sacramental life into battle. His solemn duty wasn’t to rally his comrades to victory, but to serve them dutifully in their walk through the Valley of Death, to commend their souls to God when they fell, and to bury their earthly bodies.

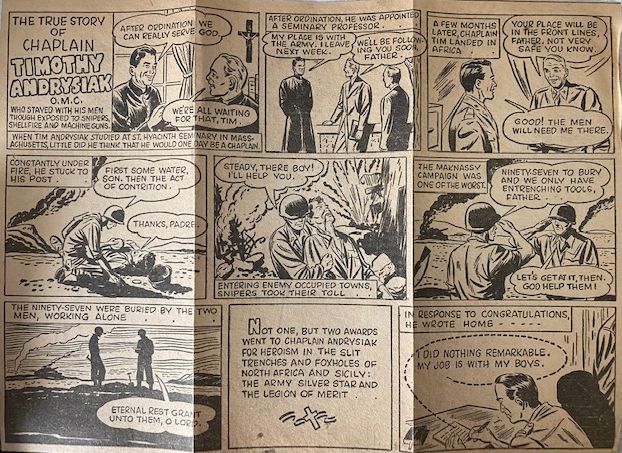

Father Timothy Andrysiak’s service is depicted in the decorations he received — a Silver Star for gallantry, the Legion of Merit, the Croix de Guerre, three Bronze Stars and the Campaign Ribbon (with eight battle stars) among them. The citations speak of extraordinary commitment to the men of his regiment and his priestly care for them.

July 30 will mark 60 years since he died, at age 55, a milestone with great meaning for his Baltimore family, who recall an uncle who gave all to his faith and his nation.

Fells Point days

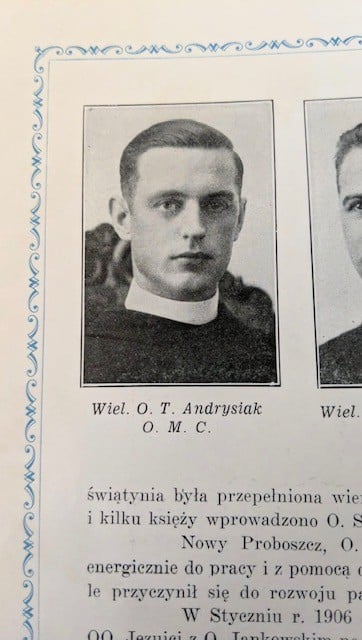

Timothy Andrysiak was born July 2, 1906, a son of Polish Catholic Baltimore, the youngest of eight. He attended the parish school at the former St. Stanislaus Kostka Church his family helped found on South Ann Street. He attended Loyola High School, and studied at St. Hyacinth Seminary in Massachusetts. He was ordained in 1929, as the Great Depression was taking hold.

He served as a parish priest in Massachusetts and Michigan, then returned to his alma mater to teach. A full year before Pearl Harbor but with global war just around the corner, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army the day after Christmas in 1940.

World War II changed the narrative for Catholics in the United States. A population that was considered suspicious and not fully American by the mainstream would swell the rosters of the U.S. armed forces, anxious to prove their loyalty as well as save the world so many had left behind in Europe.

Father Andrysiak was the first Conventual Franciscan commissioned as a U.S. Army chaplain for World War II. Part of the heroic 9th Infantry, he shipped overseas in 1942 and saw brutal action in North Africa and Sicily before arriving in the turmoil of Normandy on D-Day+4.

The work of a chaplain with a combat unit was traumatic and frightening, providing sacramental care to young men in mortal danger, celebrating open-air Masses for soldiers just fresh from combat, nursing the men who fell, anointing the dying, burying the dead — and then getting up and doing it again the next day, frequently under fire.

Burying the dead is among the Corporal Works of Mercy. A Stars and Stripes cartoon depicted Father Tim and an assistant burying 97 soldiers in a single day. The priest described it as one of the most important duties of a chaplain. He took down everything he could about each soldier, took their fingerprints, commended his spirit to God and placed the body in the ground, with a copy of all the information he was able to record in the soldier’s pocket, to be found later when the Graves Registration personnel unearthed the remains, to be moved to permanent and official graves.

His citation for maintaining his cool under fire included his being “… encouraging to the wounded and inspiring to the whole command.” The parish he was assigned to may have been a battlefield, but he was still a priest first.

He became an inspiration to the soldiers of the 9th Infantry. The March 1944 issue of Stars and Stripes tells of his defying an order restricting chaplains from approaching the front beyond aid stations, crawling through the battlefield among the fallen providing aid, comfort and assurances of God’s mercy.

One fellow soldier was befuddled to guess which incident of the chaplain’s courageous services was being recognized, because his heroism was so very much a constant: “I doubt the Army stopped to pick one out,” the man said. “There were too many of them. It could have been for any one of Father Tim’s many acts of sheer courage in trying to be where the men needed him most.”

Baltimore was never very far from his thoughts. Surveying the field for the killed and wounded following the Battle of the Bulge, he began tending to an unconscious member of the 82nd Airborne, before realizing, “I know this young man.” It was a cousin of his nephew Frank’s, the son of another family from St. Stanislaus Parish. Father Tim wrote home to his family, to let them know their neighbor was wounded but safely evacuated.

Masses were frequently celebrated using the tailgate of a Jeep for an altar table, or perhaps a board balanced between sawhorses. Father Andrysiak preferred the cover of a tree — not for shade from the sun, but because the gleaming white altar cloth might otherwise be spotted by enemy reconnaissance planes. He described Mass attendance as 80% away from combat areas, but 100% immediately before or after a battle.

The 1944 Stars and Stripes article described Father Andrysiak, in his late 30s, as having prematurely gray hair, not an uncommon reality for soldiers who endured the traumatic stress of continued enemy shelling. (Think of the white-haired actor Ted Knight who, before his Mary Tyler Moore Show days, had been a highly decorated member of the 296th Combat Engineers.)

The work of a chaplain takes a special toll. Like the neighbor he found among the Battle of the Bulge wounded, everyone was someone’s cousin. Someone’s husband. Someone’s father. A seasoned soldier tries to mentally detach from these connections and stories of the dead around them. It’s a key to survival. But a priest has no such luxury, called by his vocation to recognize and honor the unique human dignity in each soldier, and in each tragedy.

Remaining in Germany in the war’s aftermath, peacetime provided Father Andrysiak new challenges, as the next generation of soldiers arrived at what was considered a plum assignment. His deeper connection was with the wartime bonds he had created, and he stayed close with his fellow soldiers, ultimately returning with the 7th Infantry to the Korean War.

As traumatic as it was, wartime ministry was the work he knew, and the work that had come to define his vocation.

His stateside posting at Fort Meade brought him back to a family that loved him deeply, a religious order that honored his status among them, and a military that highly decorated him, but it was a world he had trouble connecting with, according to surviving family members. As a stateside chaplain, he was assigned to work with conscientious objectors, including men who had wounded themselves to escape from conscription. Having seen the horrors of the front, he could sympathize.

His brother Frank and nephew (also Frank) would drive down to the base to take him back to Baltimore for Sunday dinners and card games with the family, providing some loving respite for his burdened spirit. The younger Frank Andrysiak recalled once asking his uncle about his wartime experience, and getting a fun tale about how “scandalized” he was by General Patton’s salty language.

But of course, little of it could be described as “fun.” At age 55, heavy with emotional scars of battle and the memories of all the young men whose earthly stories ended with his anointing and burial, Father Andrysiak joined his fellow soldiers in eternity. His obituary sang of his service and honor, reminding his neighbors of the heroism of the boy from St. Stanislaus, and informing them he died of a myocardial infarction in an Ellicott City nursing home.

The best and bravest of Catholic callings often result in martyrdom, and it was a slow sort of martyrdom that took Father Andrysiak home to God. Later family research revealed he had in fact died in a psychiatric hospital, and a listed contributing factor to his death was chronic depression, an illness the medical world was just beginning to understand.

“For people in caring positions, there isn’t always someone to turn to,” said Karen Ramey, his great-niece.

It was this discovery that revealed to his adoring nieces and nephews the true measure of the burden of the uncle they had adored — and why they still recall him so vividly now 60 years after his passing.

Six decades later, a family continues to recall the true heroism of the uncle among them who witnessed the worst of times day after day, defying them as he cared for his fellow soldiers in life and death, carried their tragedies home with him, and in his witness ultimately joined them in glory.

Also see

Copyright © 2021 Catholic Review Media