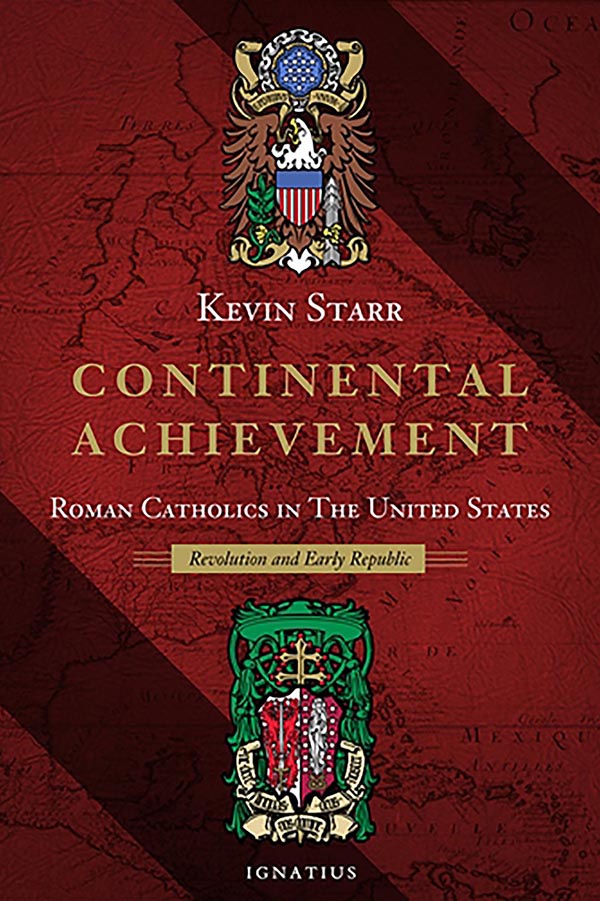

This highly anticipated second volume in historian Kevin Starr’s history of Catholics in the United States is nothing short of glorious.

Delving deeply into the story of how Catholics participated in the Revolutionary War and the early years of the new republic, Starr shows the same dedication to scrupulous research, thoughtful weighing of evidence and lively narrative style that distinguished his earlier volume, “Continental Ambition: Roman Catholics in North America.”

The American Revolution gave Catholics in North America’s English colonies the opportunity “to earn a new and better place for themselves in an emergent American republic,” Starr writes.

He casts a wide net, focusing both on Catholic leaders — such as John Carroll, “the founding bishop of Catholic America,” and Mother Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton, the church’s first American-born saint, who founded the first American congregation of nuns, the Sisters of Charity — and the substantial number of rank-and-file Catholics “who did their fair share of the fighting and dying” in the revolution.

The war’s American deaths numbered more than 25,000 and the British deaths topped 15,000. Showing respect toward the suffering endured by both sides, Starr paints a grim picture of Valley Forge.

It was, he tells us, “a valley of shadows, death and betrayal … harsh and cold.” Shelter consisted of “little more than 14-by-16-foot split-slab huts housing 12 men to a cabin,” only heated by clay fireplaces.

In characteristic detail, Starr adds: “An absence of rations for up to three days at a time was not uncommon in the first phases of the encampment. The only food consisted of firecakes, thin bread made of flour and water and baked over a campfire. Men died of hunger, as did some 500 horses. No greatcoats were available for use against freezing temperatures. Men wrapped themselves in the blankets in which they slept at night, and many were forced to tie rags around disintegrating footwear or, worse, around their bare feet.”

Starr also devotes attention to European Catholics who figured prominently in the Patriot victory, such as the Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciuszko.

And he notes the singular Baron von Steuben of Prussia, a “Catholic-friendly Calvinist” educated by Jesuits who served as master drill sergeant for the army. Von Steuben is credited with establishing the drilling norms that Patriot soldiers, who mostly viewed their bayonets as a cooking spit, desperately needed.

As he does with other figures throughout the book, Starr richly characterizes the baron. Clad in his full-dress uniform, von Steuben could swear in several languages — German, French, Russian and English.

“His multilingual profanity when his instructions were not carefully followed became a popular form of entertainment for enlisted men,” Starr writes.

Von Steuben recognized the theatrical value of his cursing (and frequently feigned) temper tantrums, yet he maintained a Prussian-style distance from enlisted men, who could not speak to him directly unless he spoke to them first.”

After the war, there were hopeful signs that Catholics were more accepted in the United States. In fact, Starr notes that during the antebellum years of 1820 to 1850, “thousands of Americans” became Catholics.

Then a huge number of immigrants from Catholic Ireland arrived, and with it, a harsh and violent anti-Catholic nativism that lasted at least into the mid-19th century. Its low point came in 1844 when anti-Catholic rioting in the city of brotherly love, Philadelphia, led to the deaths of 20 and the burning of two churches.

At the same time, though, Catholic peoples in the United States grew increasingly diverse. For instance, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 ended the war with Mexico and brought Texas and California, with their large Catholic populations, officially into the United States.

Starr details the new Catholic dioceses that were created in the American West in the early years of the republic: Cincinnati (1821), St. Louis (1826), New Orleans (1826), Detroit (1833), Vincennes (1834), Nashville (1837), Milwaukee (1843) and Chicago (1843).

One of the most interesting sections of the book describes how Mother Seton, a penniless widow and mother of five, became a Catholic and established the Sisters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Starr greatly enriches our understanding of this influential woman. His nuanced analysis explains how her loss of her beloved husband and two of her young daughters represented a “ghastly harvest of loved ones” that made her “very motherhood, the bedrock of her earthly and spiritual identity,” into “a source of pain and loss that tested her faith.”

“Continental Achievement” includes a well-detailed index and extensive essay on sources.

The late Starr, who served as the city librarian of San Francisco and the state librarian of California, was a professor of history at the University of Southern California, where he also worked as director of the Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies.

In the book’s preface, his widow writes that “Continental Achievement” and its earlier companion, “Continental Ambition,” “remain his offering to the church that raised him and sustained him throughout his life.” “Continental Achievement” alone is a crowning achievement of this gifted historian.

Anyone who wishes to understand how Catholicism established itself as a leading religion in a Protestant republic will want to read this book.

Roberts is a professor of journalism at the State University of New York at Albany and the author/co-editor of two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.

Read More Book News

Copyright © 2021 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops