The first Catholic cathedral in the United States could have been a Gothic structure, but the first bishop for the Catholic Church in America wanted something forward-looking for the new country.

Bishop John Carroll, planning to build America’s first cathedral in Baltimore, chose instead a neoclassical structure, designed by the architect of the brand new U.S. Capitol, Benjamin H. Latrobe. He presented two plans, one Gothic, one neoclassical.

At that time, neoclassical was considered modern, noted John G. Waite, the principal architect for the basilica’s 2006 restoration. With its pillars, portico and prominent dome similar to buildings rising in the new American capital of Washington D.C., it was more in keeping with the sensibilities of the American public.

“It’s really an important collaboration between Bishop and Archbishop Carroll and Latrobe,” Waite said. “It’s actually extraordinary and very important because John Carroll wanted a symbol for the Catholic Church that would look to the future and would be a symbol of the importance of the church in the United States.”

Waite, who heads a historic preservation firm in Albany, N.Y., that bears his name, noted that when the cathedral was built, there were barely enough American Catholics to fill it.

“Only a few decades earlier, Catholics were a persecuted minority in America,” he told the Review.

Bishop Carroll chose the neoclassical plan, with modifications, and the cornerstone was laid July 7, 1806.

What Latrobe designed was unlike any other cathedral in the world, according to Duncan Stroik, professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, and founding editor of the Sacred Architecture Journal.

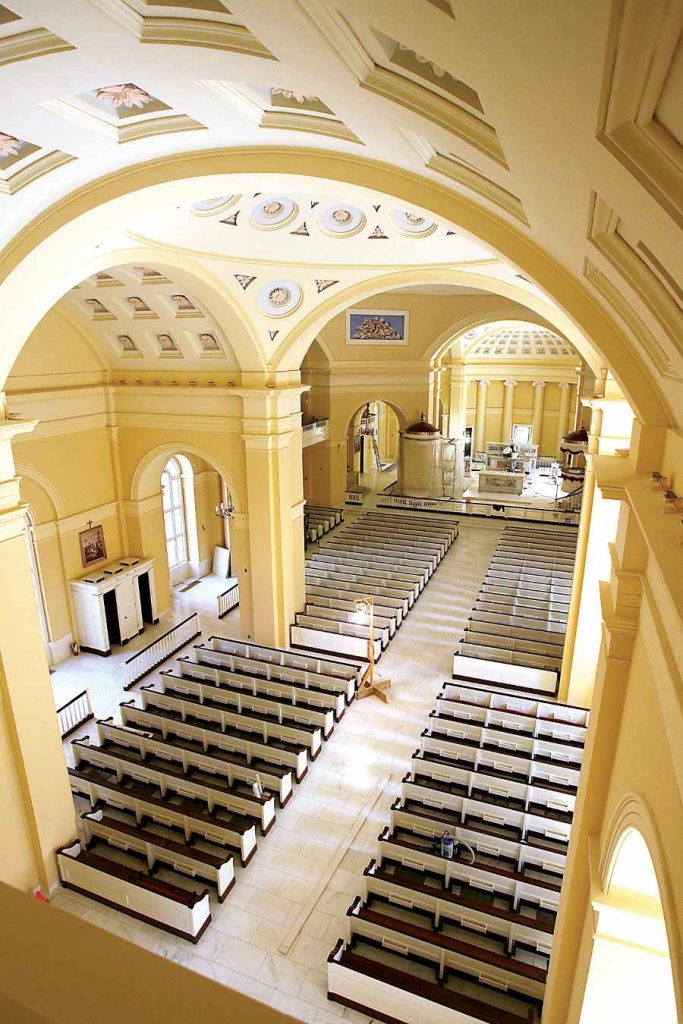

There were no stained glass, no statuary around the front door, no flying buttresses, all typical of Gothic style. Instead, Latrobe designed an entrance with pillars and a portico, with a great dome, and built of stone.

“We expect a cathedral to be beautiful, triumphant, permanent, vertical,” Stroik said. “We associate stone with permanence.”

Stroik praised the selection of Latrobe, an Englishman considered to be the first professionally trained architect. Latrobe, who donated his work, counted George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, himself an architect by avocation, among his friends.

Listen to an interview with Duncan Stroik on the history and architecture of the Baltimore Basilica below. Story continues beneath.

Among his notable designs were the U.S. Capitol, where a classical theme incorporated American floral motifs, corn cobs and tobacco leaves, and the restoration of the White House after the War of 1812.

“The only building in the United States that compared with the basilica in sophistication and size was the U.S. Capitol,” Waite added.

Among Latrobe’s plans were skylights for the basilica’s dome, but the leaky dome at the Capitol forced him to rethink how they should be added. He directed the addition of 24 skylights on the sides of the main dome – where they’d be less likely to leak.

“It has been a wonderful solution,” Stroik said.

The skylights, restored in the 2006 project, along with the return of clear glass windows, fill the sanctuary with light. At the time of the dedication, people described the interior light as “almost magical,” Waite said. “People were really bowled over by it.”

Baltimore’s then-cathedral, set on a hill, was innovative, symmetrical and filled with tradition, according to Stroik. Though not large by today’s standards, it was the biggest church in the original Thirteen States.

“At the time it was a really big church for the new republic,” he said.

Over the 15 years of construction and the years since, the basilica has seen many changes. The portico differs from Latrobe’s design. The towers were added later. When the semicircular apse behind the altar was enlarged in 1890, it was in keeping with Latrobe’s vision, according to Waite: “The cathedral needed a large sanctuary to function.”

“All the additions work well with the building,” Stroik said. “It seems like they fit with the building.”

Restoration also uncovered Latrobe’s reverse arches in the crypt that hold up the weight of the great church’s domes and pillars, “an innovative idea,” Stroik said. The crypt now houses a chapel and exhibit space.

The original west balcony over the entrance was restored in 2006, Waite said. Bishop Carroll ordered it to serve free African Americans of Baltimore.

“It was very important, very progressive at the time,” he said. “Cardinal (William) Keeler realized in the 21st Century, if the church was going to assume a leadership role in the City of Baltimore, it was important symbolically to put that balcony back.”

Construction of the new cathedral took 15 years, due to a number of vexing delays, including the War of 1812, which brought a complete suspension of construction, according to Thomas W. Spalding, in his history of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, “The Premier See.”

In the fall of 1818, Latrobe wrote to his son, “Yesterday we closed with some ceremony & a great deal of push the dome of the Cathedral (and) 3 cheers given, which resounded half over the city,” according to Spalding’s history.

Neither Archbishop Carroll nor Latrobe would see the cathedral’s completion. The third archbishop of Baltimore, Ambrose Marechal, oversaw the last phase of construction and presided at its dedication May 31, 1821, with work on the portico and towers still unfinished.

“After 30 years of common effort, the Archdiocese of Baltimore had erected one of the finest churches in America,” wrote Archbishop Marechal.

Stroik agrees. “It’s a little gem,” he said. “It’s one of our great cathedrals.”

Also see

Copyright © 2021 Catholic Review Media