Witnessing thousands of South Africans of all races vote in the first free elections after the fall of apartheid was a “great, life-changing experience” for Bishop John H. Ricard, S.S.J.

“It was a very exhilarating experience to see old enemies finally reconciling and to actually see the birth of a country,” remembered Bishop Ricard, a former auxiliary bishop of Baltimore, from 1984 to 1997, who was an official electoral observer in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, during the April 26-29, 1994, election.

“We saw people who had never voted in their life — old people and young people,” Bishop Ricard said. “It was a period of joy and jubilation.”

Bishop Ricard credits Nelson Mandela, the man South Africans elected as their president, for being a driving force behind making the historic election possible and for overseeing a peaceful political transition.

Mandela, who died Dec. 5, was released from prison in 1990 after 27 years. As the nation’s first black president, serving from 1994 to 1999, he promoted peace and reconciliation.

“He was able to forgive and be reconciled with the people who oppressed him for so long,” said Bishop Ricard, retired bishop of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Fla., and current rector of St. Joseph’s Seminary in Washington, D.C.

Mandela “literally saved South Africa from itself in the process,” said Bishop Ricard, calling the former president an “effective leader who rose above the differences in race and culture and hate.”

“He was able to lead South Africa to become a new country,” the bishop said. “It became a beacon to all of Africa and all the world.”

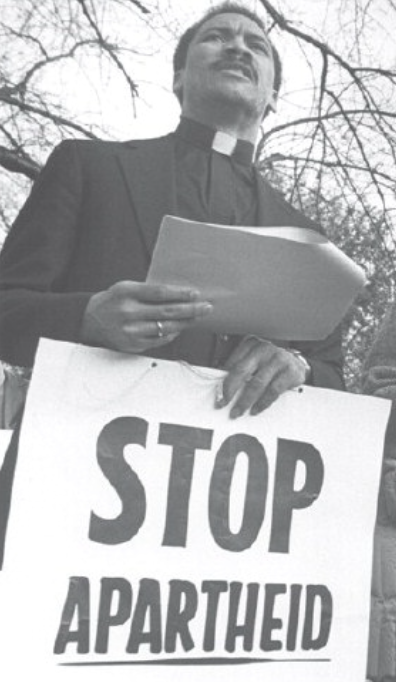

While in Baltimore, Bishop Ricard, one of the U.S. church’s African-American Catholic bishops, had been active in the anti-apartheid movement, participating in prayer vigils and anti-apartheid planning sessions in Baltimore and Washington. He put pressure on the U.S. Congress, the Reagan administration and the State Department to support sanctions against the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Congress passed economic sanctions in 1986, overriding President Reagan’s veto. When the sanctions became intolerable to the apartheid regime, Bishop Ricard said, apartheid leaders “finally came to their senses” and released Mandela.

Bishop Ricard met Mandela during a 1990 visit to the Riverside Church in New York after Mandela’s release.

“He said that we should all overcome as he did,” Bishop Ricard recalled, “and all strive for reconciliation and for peace among ourselves — to love our neighbor, which he showed and lived.”

Bishop Ricard, a member of the Baltimore-based Josephites, emphasized that Mandela was not perfect.

“With the anti-apartheid struggle, there were things that happened and offenses on both sides, but overwhelmingly on the apartheid side,” he said.

Yet, Bishop Ricard called Mandela an “extraordinary man who endured a great deal.”

“He belonged to South Africa,” Bishop Ricard said. “Now, he belongs to the ages.”

Email George Matysek at gmatysek@CatholicReview.org

Copyright © 2013 Catholic Review Media