As the world marks the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Catholic Church must renew its commitment to nonviolence, disarmament and lasting peace, said U.S. prelates attending commemoration events in Japan.

Cardinal Robert W. McElroy of Washington, Cardinal Blase J. Cupich of Chicago, Archbishop Paul D. Etienne of Seattle and Archbishop John C. Wester of Santa Fe, New Mexico, traveled to Japan for an Aug. 5-10 “Pilgrimage of Peace.” The delegation, which included faculty, staff and students from several U.S. Catholic universities, was welcomed and accompanied by Archbishop Peter Michiaki Nakamura of Nagasaki and Bishop Alexis Mitsuru Shirahama of Hiroshima.

In a joint statement issued Aug. 6, the bishops on the pilgrimage, along with Catholic bishops from Japan and South Korea — as well as a number of atomic bombing survivor organizations — strongly condemned “all wars and conflicts, the use and possession of nuclear weapons, and the threat to use nuclear weapons.

“We refuse to accept persistent justifications for atomic bombings as a means of ending war,” said the statement, which advocated for the ratification and expansion of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, as well as cooperation with its articles on supporting victims and environments harmed by such armaments.

The pilgrimage was the third for Archbishop Wester, an outspoken advocate for nuclear disarmament, who in 2022 issued the pastoral letter “Living in the Light of Christ’s Peace: A Conversation Toward Nuclear Disarmament.” The Santa Fe Archdiocese is home to both the Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories, longtime critical facilities in the U.S. nuclear weapons program.

On Aug. 6 — the feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord — Cardinal Cupich presided over a Mass for peace in Hiroshima, where on the same day in 1945 the U.S. dropped the first of its two atomic bombs on Japan, with a second targeting Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945.

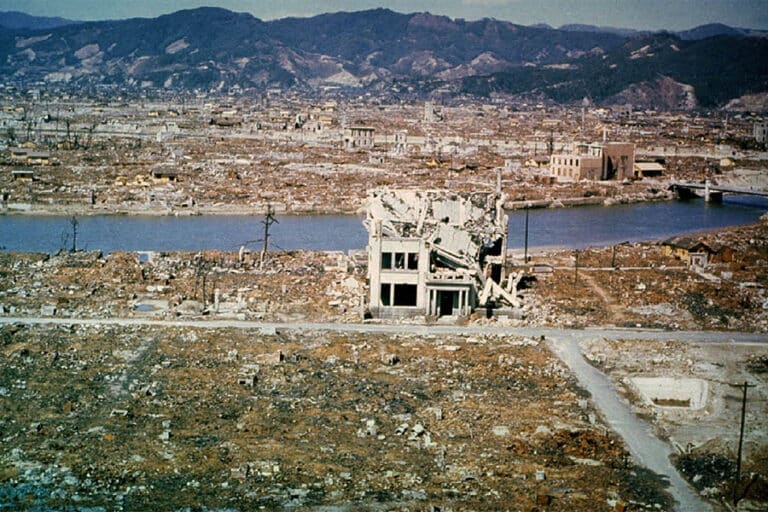

The bombings — intended to force Japan’s unconditional surrender in World War II — killed an estimated 110,000 to 210,000 people. The range is attributed to both the cities’ own incomplete record-keeping and the sheer scale of destruction.

Cardinal Cupich reflected in his homily that the light of Jesus Christ’s transfiguration on Mount Tabor “revealed our calling to share eternally in divine glory as sons and daughters of the Father.” But in Hiroshima, he said, “light brought unimaginable destruction, darkness and death.”

The cardinal drew a stark parallel between the science of nuclear fission and the explosive consequences of strife and hatred.

“Physicists tell us that the blast occurs when a neutron divides the nucleus of an atom,” he said. “The same is true when we sow division, stoking impulses of anger, resentment and bigotry. These unchecked emotions spiral out of control, creating a destructive chain reaction that blinds us to the vision God has always wanted for us.”

“The world witnessed the alarming misuse of human ingenuity that brought about inconceivable destruction,” Cardinal Cupich said. “So this morning, we are called to sustain and make our own the vision God has always had for us … by creating new paths towards a lasting peace.”

In an Aug. 6 address during an academic symposium at Elisabeth University of Music in Hiroshima, Cardinal McElroy shared his thoughts on renewing Catholic teaching on war and peace, amid soaring geopolitical tensions and military spending.

“There is no more sacred place on this planet” to discuss peace than in Hiroshima, “where the fullest horrors of war have been unleashed upon humanity,” said Cardinal McElroy. He noted as well the “unsurpassed depth” of the “heroism and hope of the Hibakusha,” referring to the survivors of the atomic bombings.

He described the “overwhelming violence” of World War II, culminating in the atomic bombings, as an inflection point for humanity. He said it demanded the world “confront the very reality of war at its core” and the “spiritual and moral failures” underlying such carnage.

“At the very center of this profound reflection was the searing recognition that atomic weapons were not merely a new type of warfare, but a human creation that would have the capacity to end humanity itself,” he said.

Pope St. John XXIII’s 1963 encyclical, “Pacem in Terris” — written shortly after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, which saw the U.S. and the Soviet Union in a nuclear weapons standoff — “set forth a comprehensive framework for building authentic peace in the world” by articulating fundamental human rights essential to peace, said Cardinal McElroy.

Moreover, said the cardinal, Pope John “fearlessly proclaimed that the issue of nuclear weapons was at its heart a moral question, and that the world would have to forge a way toward nuclear disarmament if the future of humanity was to be assured.”

“Ever since ‘Pacem in Terris’ was written, every successive pope has pointed to the moral depravity of war,” he said.

Just as Pope John “created a new moment in Catholic thought,” the current moment has witnessed “three major shifts in Catholic thinking,” said Cardinal McElroy.

“First, the continuation of wars among nations and within societies, enlisting devastating weapons and resulting in countless deaths have pointed to the need to fundamentally renew and prioritize the claim of non-violent action as the primary framework for Catholic teaching on war and peace,” he said.

More than 120 conflicts are currently taking place throughout the world, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross. Military spending has soared, with the global total reaching a record high of close to $2.5 trillion in 2024, up more than 7% from 2023 and averaging almost 2% of nations’ gross domestic product, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Second, Cardinal McElroy also pointed to the “continuous misuse of the just war tradition,” the church’s ethic on armed conflict that draws from the thought of St. Augustine. As explained in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, legitimate defense by military force is morally permitted under strict conditions all present at one and the same time: the “lasting, grave and certain” damage from the aggressor, the exhaustion of all other efforts to end such damage, “serious prospects of success,” and the use of arms such that graver evils and disorders are not produced.

While just war criteria have often historically prevented or mitigated war — and “while in limited circumstances, such as Ukraine, a recourse to war is morally legitimate within limits and in response to attack” — he said the tradition “must be revisited and refined it if is to provide compelling moral guidance in the contemporary world.”

“Many elements of modern warfare have conspired to limit its power as a constraint on war, which was the tradition’s only reason for existence,” said Cardinal McElroy.

Instead, in a number of recent instances, the just war framework “has operated as a source of justification for those inclined to go to war rather than as a constraint on war,” he said.

Lacking a “realistic set of moral criteria” for seeking to end war, the tradition also fails to fully account for the modern geopolitical landscape, which includes “complex alliance, failed state and non-state actor realities,” he said. “The current horrors in the Middle East illustrate this. Every side justifies its actions morally, and the just war tradition provides little concrete guidance.”

Third, while “consistently, the church has demanded that nuclear weapons be eradicated from the face of the earth,” he said the successors of Pope John XXIII have increasingly stressed that nuclear deterrence is not a long-term viability. He noted that “Pope Francis categorically condemned the possession of nuclear weapons as morally illicit.”

The cardinal underscored the need for collective action to eliminate the world’s nuclear arsenals. He pointed to this year’s “alarming confrontation” between India and Pakistan, and U.S. strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities that he feared could have the unintended consequence of teaching nations that ownership of nuclear weapons is the only way to prevent a nuclear attack.

“If our gathering here today is to mean anything, it must mean that in fidelity to all those lives destroyed or savagely damaged (on Aug. 6 and 9, 1945) … we refuse to live in such a world of nuclear proliferation and risk-taking,” he said. “We will resist, we will organize, we will pray, we will not cease, until the world’s nuclear arsenals have been destroyed.”

Also read:

Maryland Catholic Conference pleads for peace on 80th Anniversary of atomic bombings

Pope calls for nuclear disarmament, real commitment to peace

Peace, disarmament begin in the heart, said Archbishop Broglio

Read More World News

Copyright © 2025 OSV News