On a windy hill in the north of Ireland, I visited a grave claiming to be St. Patrick’s. A couple of other sites vie for that honor, but this hill is a deeply moving place.

During St. Patrick’s season, my thoughts turn to two other Irishmen on the road to sainthood.

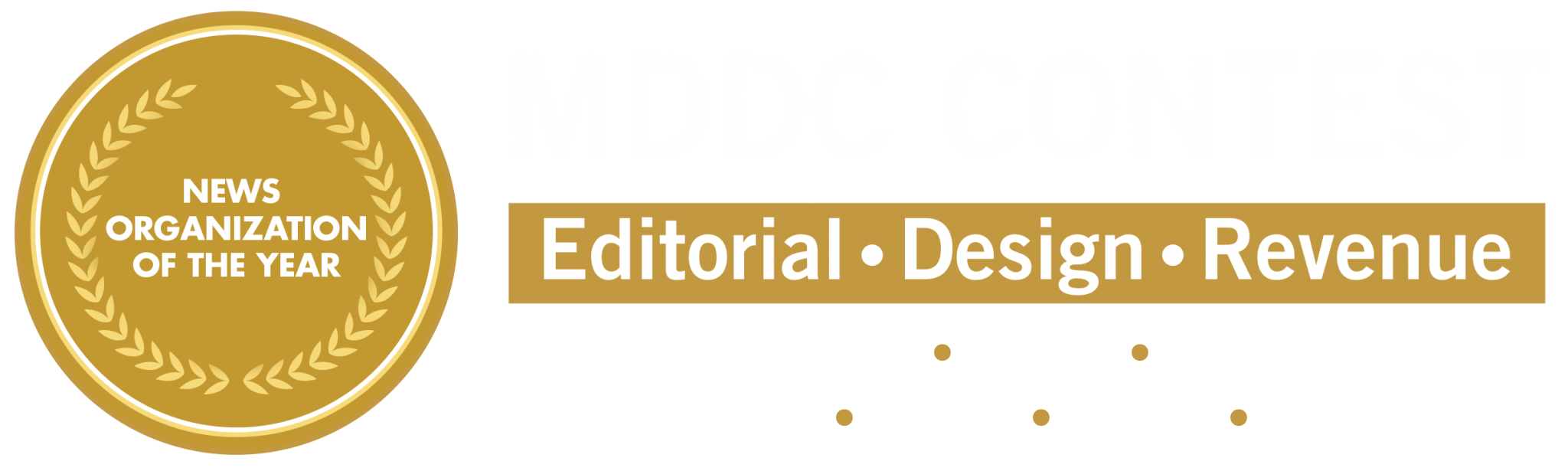

There’s Blessed John Sullivan, born in 1861, a handsome man, the scion of a prominent family. Someone once called him “the best dressed man in Dublin.”

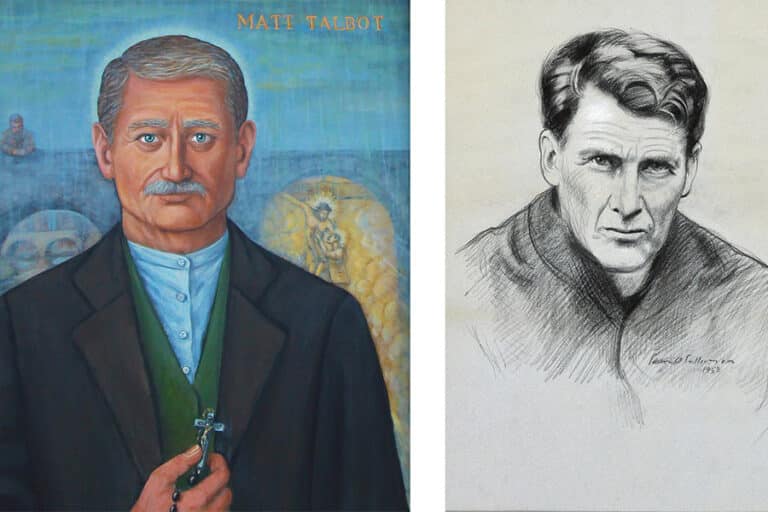

Then there’s Venerable Matt Talbot, born in 1856, the child of an impoverished alcoholic, whose own chronic alcoholism brought him to his knees and now to the portal of sainthood.

I imagine these two Irishmen, contemporaries, passing each other unaware on the mean streets of Dublin sometime in the early 20th century. They remind me of that old adage, “Every sinner has a future, and every saint has a past.”

Sullivan’s mother was Catholic; his father, destined to become the Lord Mayor of Dublin, was Protestant. In that era’s tradition, girls were raised in the mother’s faith, boys in their father’s. Sullivan studied at Protestant schools, then Trinity College in Dublin. He studied law in London. Later, he acknowledged his Protestant upbringing with inspiring his early spirituality, and an Anglican bishop attended his beatification ceremony.

In 1896, Sullivan became a Catholic, and always credited his mother’s prayers with his conversion, just as St. Augustine credited St. Monica. (Take heart, moms!) Sullivan became a Jesuit, and spent years teaching at Clongowes Wood College in Kildare, Ireland, where his stylish wardrobe was replaced by a worn black cassock. He earned a reputation as a healer, and went about the countryside on his bike visiting the sick.

Until his dying day, he carried his mother’s crucifix with him, and it is with him at Gardiner Street Parish in Dublin where he now lies in repose.

Matt Talbot had a much different life trajectory. We have only a grainy portrait of Talbot. After attending school very briefly, he went to work to help support his family. As a 12-year-old, he returned bottles for a Dublin liquor merchant and discovered the dregs at the bottom of those bottles.

Becoming a teenage alcoholic, Talbot often relied on friends to supplement his meager wages with money for his growing habit. In his late twenties, he had an epiphany and took “the pledge,” an Irish promise of abstinence. But in those days before Alcoholics Anonymous, it was a lonely struggle. Talbot increasingly turned to his faith and a life of penance, prayer, Mass and mysticism. A committed union man and building laborer, he joined the Secular Franciscan Order.

Talbot would have died in obscurity, but when he was found dead of a heart attack on his way to Mass in 1925, chains encircled his body under his clothing, at that time the mark of an ascetic and deeply penitent man.

One story I find particularly touching: As an active alcoholic, in his desperation for a drink, Talbot once stole the fiddle of a blind man who used music to beg for alms. After embracing sobriety, he searched futilely for the blind man to repay him. Maybe his deep regret makes those chains easier to understand.

People flock to the Gardiner Street Jesuit parish, where you can see Sullivan’s tomb on the parish website’s webcam. Alcoholics all over the world beg Talbot for prayers.

“Venerable” means Talbot’s cause for sainthood has been accepted and awaits a miracle to move to the next level, “Blessed.” Blessed John Sullivan’s cause awaits a second miracle before canonization. St. Patrick, pray for them, and for us.

Read More Commentary

Copyright © 2025 OSV News