Most immediately apparent upon entrance is the brightness.

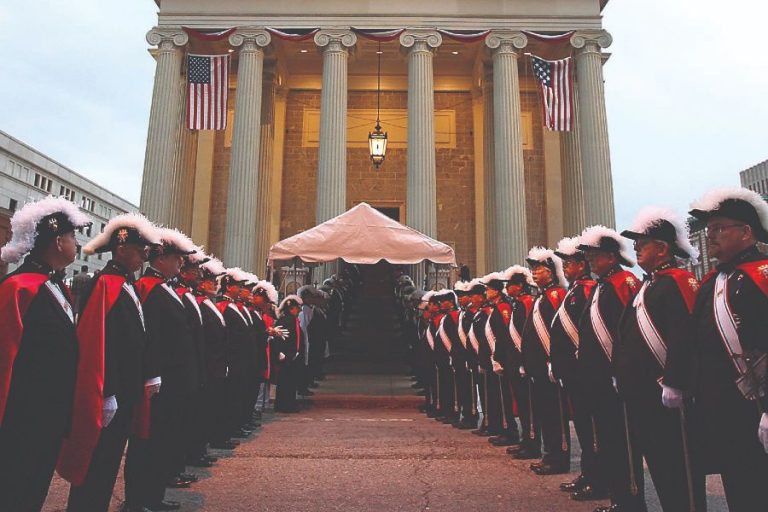

“On a sunny day, visitors would walk in and get knocked down by the light,” said John Igoe, one of around 25 docents who until recently accommodated a steady stream of visitors to the country’s first cathedral, the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Baltimore.

Architect Benjamin Latrobe planned it so. He and then-Bishop John Carroll – Baltimore’s and America’s first bishop, soon to become archbishop – opted for clear windows and a white color scheme to include the gleaming marble floors and painted pews as well as the walls. The sky-lit dome was reportedly the product of a design compromise between the two men, mediated by Thomas Jefferson, who had identified a suitable style window during a trip to Paris.

“We have his letter to the bishop,” Igoe said.

He offers a clear and informative explanation of the design, history and purpose of America’s first cathedral in his video, “The Baltimore Basilica – A Short History,” available on YouTube.

The basilica’s history ties in directly with the history of the church in America, shaped by the principle of religious freedom.

Turbulent beginnings

Igoe’s video notes that several states refused to ratify the U.S. Constitution until the Bill of Rights, a list of amendments guaranteeing certain popular freedoms, was added.

The very first independent clause of the first of those amendments states: “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of a religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof …”

The writers and signers of that simple statement could not have anticipated the particularities of the arguments that have coalesced, today as intensely as ever, around it. But by putting it to paper, they affirmed, at least, that all believers in the nation they were establishing would have the standing to wage or answer such arguments.

The guarantee not only held up a lofty ideal, but also secured the nation’s legitimacy by protecting against the folly of legislating that which would not be obeyed.

Founded by the Catholic convert George Calvert, known by title as Lord Baltimore, Maryland alone among the Thirteen English Colonies protected its citizens’ right to conduct their lives as had been written on their hearts. Then as now, the citizens and their leaders sometimes or often failed to live up to that. Meanwhile, Protestants immigrated, the colony changed and Catholics were outnumbered, though they still held the larger share of political and economic power.

History suggests that George Calvert’s grandson, Charles Calvert, attempted to maintain that power by tilting governance and influence even more transparently toward those elites. Probably most consequential was the decision that African slaves and their children would remain so for life, despite the belief of some at that time that slaves should become free after Christian baptism.

The Calverts lost control of Maryland, and in the 1700s the colony became subject to the same “anti-popery” laws common in the other colonies. Nevertheless, Catholicism remained, though Catholics were not allowed to vote or run for election, and Mass was celebrated in homes or in “churches disguised as homes,” as fellow basilica docent William Moeller narrates in Igoe’s video.

Establishing a home

The humiliation was apparently healthy for the church. When the Bill of Rights in 1791 formally recognized freedom of religion, Maryland had Catholics in numbers such that Pope Pius VI had ordained John Carroll two years prior, and Bishop Carroll had already been charged with building a cathedral from which to lead his diocese, which encompassed what was then the whole U.S.

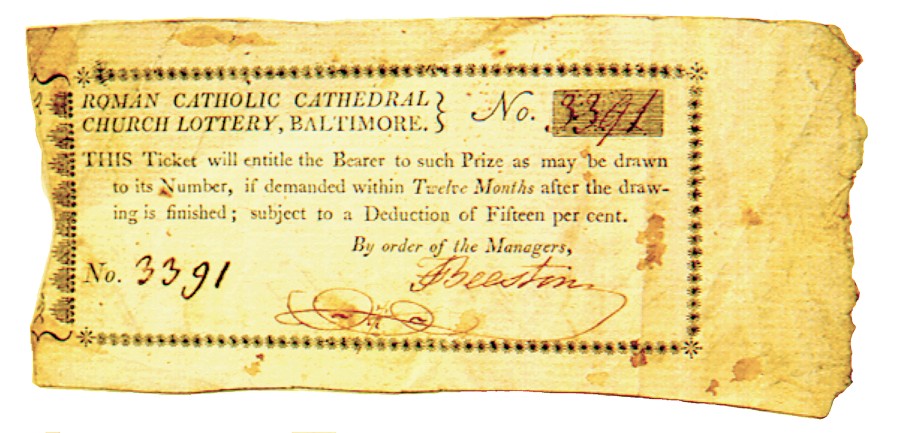

In a column penned at the beginning of Lent in 2006, Catholic writer George Weigel wrote that the construction of the cathedral was financed through a lottery.

Weigel recounted how, “as luck would have it, Archbishop Carroll, reaching into hundreds, perhaps thousands of lottery tickets to choose the winner, picked his own ticket – and promptly gave his winnings back to the building fund. (Nary an eyebrow was raised.)”

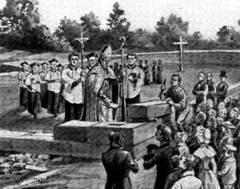

The cornerstone for the cathedral was laid in 1806, but the building was not opened for worship until 1821. The delay, according to Igoe, is attributable to funding difficulties, the War of 1812, and arguments over the design, especially of the aforementioned dome.

There is not a lot of surviving paperwork regarding the actual labor, Igoe said. What is known is that the workers were local, Baltimore bricklayers.

The undercroft, newly unearthed and opened to the public following the basilica’s 2006 renovation, exhibits their unusual and pragmatic handiwork, which answers the majesty of the upper building with an equal measure of mystery. Rather than a deep foundation fused into the bedrock, “inverted arches,” made of brick and not so deep, support the basilica’s soaring dome.

Over the last 200 years, humans have made decisions of great consequence and resolve while gazing on the basilica’s high altar, sanctuary angels, and understated artwork in keeping with the building’s neoclassical design.

The consecration of more than 30 bishops, the commissioning of the Baltimore Catechism, the planning of the American Catholic school system and the first ordination on U.S. soil of an African American priest all occurred there.

Christ hanging on the cross behind the altar reminds all of their need for redemption, and great sins are owned and expiated steps from where the noblest plans are hatched.

“For me, it’s the whole proof of the Catholic Church,” Igoe said, “that it’s still here despite ourselves.”

Key moments in the history of the basilica

1789

Pope Pius VI decrees that Baltimore’s first bishop, John Carroll, erect a church “in the form of a cathedral” to serve the Premier See of the Catholic Church in America.

1806

With the laying of its cornerstone, construction begins on the first Catholic cathedral in the United States.

1821

The cathedral opens to the public, although the work on the structure would continue for decades.

1832

The cathedral is the site of the funeral of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the sole Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence.

1863

Delayed by a lack of funding, work is finally completed on the massive neo-classical portico at the entrance of the cathedral.

1884

The Third Plenary Council, the largest meeting of Catholic bishops held outside Rome since the mid-16th century Council of Trent, commissions the Baltimore Catechism. The book would become a standard of Catholic teaching in the 19th and 20th centuries.

1887

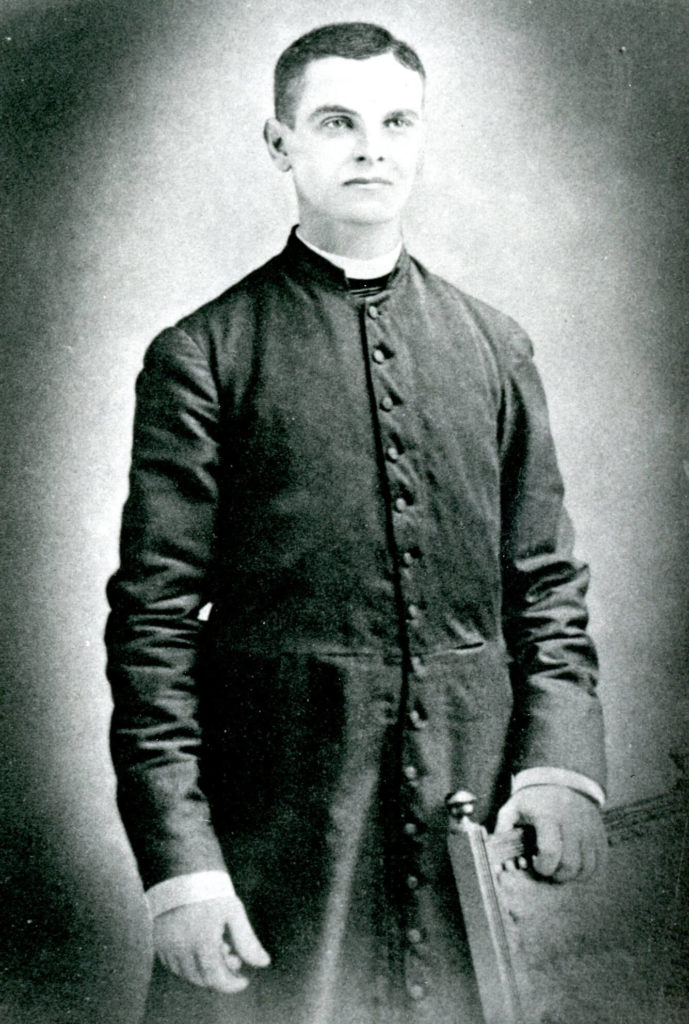

Blessed Michael J. McGivney, founder of the Knights of Columbus, is ordained at the cathedral, one of the thousands of American priests ordained there.

1891

Josephite Father Charles Uncles, of St. Francis Xavier Parish in Baltimore, becomes the first African American ordained to the priesthood on American soil when Cardinal James Gibbons administers the sacrament of holy orders at the Baltimore Basilica.

1921

Approximately 150,000 file through the cathedral to pay their respects to Cardinal Gibbons, the longest-serving archbishop of Baltimore, after his March 24 passing.

1937

Pope Pius XI designates the cathedral as a minor basilica. It’s currently one of only 89 religious buildings in North America to have that distinction.

1969

The basilica, now a co-cathedral, is added to the U.S. Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places.

1972

The U.S. government names the basilica as a national historic landmark.

1993

U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops designates the basilica as a national shrine. The cathedral is now known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

1995

St. Pope John Paul II visits the basilica as part of his historic visit to Baltimore.

1996

More than 1,000 people crowd into the basilica as St. Teresa of Kolkata receives the vows of 35 women who had joined her religious community, the Missionaries of Charity.

1997

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople participates in an ecumenical prayer service – the first time an ecumenical patriarch led a prayer service in a Catholic church in the United States.

2006

The basilica reopens after a $34 million, multiyear renovation to restore the original vision of architect Benjamin Latrobe.

2011

A rare East Coast earthquake does significant damage to the basilica. Repairs last for months and cost about $3 million.

2021

The basilica celebrates its 200th anniversary, unveiling a newly restored adoration chapel named in honor of St. John Paul II, which will be open to the public 24 hours a day.

More coverage of the Baltimore Basilica

Copyright © 2021 Catholic Review Media