Recently, it has been reported that Pope Francis mentioned that the Lord’s Prayer may be able to be translated a little better. In an interview as part of an Italian television series that focused on the Our Father, the pope mentioned that “and lead us not into temptation” might be misleading for some people – as if God was the one who “pushes” us into trouble. The French bishops have recently adopted a translation of the Our Father that is similar to the Spanish and Portuguese, which renders the line in question as “do not let us fall into temptation.” The pope commented that maybe that is a better way to go.This has caused quite the stir (as most of the comments of the Holy Father can when reported willy-nilly). People are accusing Francis of “changing the Our Father.” I heard a Protestant minister even say that Francis was “taking words out of the prayer.” A closer understanding of this particular papacy and the translation of the prayer would serve to alleviate some of the disconcert.

While I am certainly no Scripture expert, I did have to suffer through Biblical Greek; and, for better or for worse, a lot of that has stuck with me. At the beginning of each Greek class, Father Tobin would make us recite the Our Father (or Páter hêmôn) in Greek. We fumbled and tripped and – I am sure – offended our guardian angels with our attempts. However, the study of the language of the Gospels left a lasting imprint on me, and I can never read the Scriptures the same again.

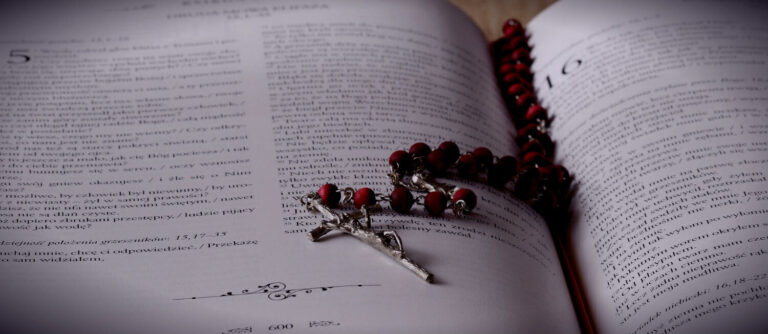

It is beautiful, in fact, to get so close to the language of the early Church (even if it is the written and not spoken language) and to enter into the heart of God’s Word. St. Thérèse of Lisieux once noted, “If I had been a priest I should have made a thorough study of Hebrew and Greek so as to understand the thought of God as he has vouchsafed to express it in our human language.”

With that in mind, I want to offer a parsing of the Lord’s Prayer as Matthew presents it in Greek (Matthew’s is the source of the prayer we pray today; Luke’s version is simpler). My hope is that it can help us all delve deeper into the heart of Jesus, who offered these words to us as a sacred gift.

Here we go:

Páter hêmôn ho en tois ouranois

“Our Father who is in heaven” – a very straightforward, easily-translated phrase. There is not much ambiguity here.

Hagiasthêto to ónoma sou

“May your name be treated as holy (or sanctified).” The tense of this verb indicates that the action is not simply a one-time thing. In other words, the sanctification of God’s name is to be a habitual action on behalf of the Christian.

Eltheto hê basileia sou

“May Your Kingdom/Reign/Dominion come.” Again, the tense indicates that this “coming” is an ongoing, never ending breaking-in of God’s kingdom.

Genethêto to thélêma sou

“May your will be done.” The verb here is a complex one. At its root, it means “to be” or “to come into existence” (it’s related to the word “Genesis”; however, when used in the context of a desire (as indicated by the noun “will,” the verb denotes that this desire or will be fulfilled – that is, that God’s will is to come into being as a fact.

Hôs en ouranô kai epi gês

“In heaven as well as upon earth.” This is a grammatical construction that is meant to link the two elements of the sentence as comparable or even equal (“as this, so too that”). Here, the idea conveyed is that the will of God that is to be done is to be the same on earth as it is in the perfection of heaven.

Ton arton hêmôn ton epiousion dos hêmin sêmeron

“Our necessary daily bread give to us today.” This is an interesting line. We imagine often that it simply means that we ought to have something to eat each day. However, it goes deeper than this. The word epiousion, literally means “necessary for existence.” Typically, in the Middle East, bread is more than just a side dish; it is often the instrument to pick up the many sauces, dips, and other foods that we eat. Therefore, without this “needful bread,” we cannot eat. Also, the verb “to give” is in a tense that does not imply a one-time giving. Rather, it conveys a sense of “give to us – and continue giving to us” this bread. Therefore, the sense of this line is “Give us today (and tomorrow and ongoing) our daily bread that we need, and keep giving us that bread, please.”

Kai áphes hêmin ta opheilêmata hêmôn

“And forgive us our debts (sins/what is owed).” The meaning of this line is relatively simple. The words can be more or less directly translated. The term opheilêmata literally means “things that are owed,” but in the Aramaic context of Matthew’s gospel, it would be understood as “sins.” Again, the verb tense would connote that the forgiveness we are begging is not just a one-time nicety, but an ongoing attitudinal practice of God toward us.

Hôs kai hêmeis aphêkamen tois opheilêtais hêmôn

“As also we have forgiven those who owe us/those who sin against us.” This is always a tricky part of the Lord’s Prayer for the Christian. We are basically placing terms on our expectations of God’s forgiveness. In the measure that we forgive others, that is how we ask God to forgive us! Jesus even underscores this in the lines immediately following the prayer: “For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly father will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your father forgive your trespasses.” The verb tense of “we forgive” indicates that we have already forgiven – and that forgiveness is our usual disposition toward those who offend us. Easily said; not easily done!

Kai mê eisenénkês hêmas eis peirasmon

“And do not lead us (do not allow us to fall) into temptation.” This phrase can have two different translations – both would be correct. The overall connotation of the line would be to ask God to regularly keep us safe from temptation. The indication is not, however, that God “leads” people into the negative aspect of temptation – like throwing a banana peel in front of us to see if we slip. Rather, when the word peirasmon (temptation/trial/ test) is used in reference to God, it is for the purpose of proving someone (cfr. Wisdom 3:5 – “For God tested them and found them worthy of himself”). The Greek need not make any distinction in the richer meaning; however, any other translation would. The Spanish – and now the French – translation of the Lord’s Prayer goes the route of “do not allow us to fall into temptation”), but the English (and Latin, Italian, German, Polish, Arabic, Swedish, etc) is an accurate translation of the Greek.

Alla rhusai hêmas apo tou ponerou

“But deliver (rescue/snatch away from) us from evil (the Evil One).” The final line of the Our Father is a petition for God to save us – literally, “to snatch out of the grip of evil.” A very straightforward line, with the exception of the possible dual meaning of “evil” or the “Evil One” himself (i.e., the devil).

Translation is an art. Language is a rich reality. When you hear the phrase, “Something is lost in translation,” there is much truth behind it. It’s like taking water vapor and solidifying it as ice – you’re stuck with the shape it takes. Words, because of the history of language and culture, have more than one meaning; and this meaning does not need to be nuanced for the native speaker. However, the Greek of the Bible doesn’t really exist anymore. Modern Greek descended from it, but it is as different in many cases as modern English is from Chaucer’s tongue. The ideal would be for us all to learn the Biblical languages – along with the history and cultures that influenced them – and to read, pray, and worship in them alone. Jesus himself spoke Aramaic as his common language (and the original offering of the Our Father would probably have been in Aramaic). He probably knew Greek because it was the language of trade, which his father Joseph would’ve spoken as a tradesman. He also would have known Hebrew, which was the language of the synagogues and temple. There is no indication of what Jesus “knew” as a man that would be any different than any other person of his day and circumstance.

The nature of language is to communicate – to establish a relationship between two people or groups. When languages are different, communication is hard. When they are the same, it is easy – and, in fact, when culture, history, and relationships are so deeply ingrained, language is often not even necessary. Think of spending time with your spouse, just being in one another’s presence; think of spending an hour in front of the Blessed Sacrament. No words are necessary; and, in fact, they could even get in the way! Knowing a little of the deeper context of the Lord’s Prayer can help us to let go of our logical minds and allow God to transform us at the level of language and heart. No words are needed, but Jesus gives us these.

Personally, I hope we keep our current translation. It is a joy and blessing to pray these words with my Protestant sisters and brothers whenever we are together. The point of the Lord’s Prayer is that this is how Christ offered us language to pray on a regular basis. There is a reason why we pray the Our Father daily. It’s “our prayer.” The wording that we use is important, but it is helpful to remember that the Bible didn’t drop out of heaven in English. If a more accurate translation is possible, that is what we have Scripture scholars for. So, before anyone flies off the handle at the Holy Father for his comments in an Italian interview, we should step back and pray an Our Father for him and for the Church. While you’re at it, say one for me (I never mastered all that pronunciation!).